Most people who have commented (outside of China) on Supreme People’s Court (SPC) President Zhou Qiang’s March, 2017 report (on 2016 work) to the National People’s Congress (NPC) didn’t have the patience to read (or listen) much beyond the initial section, which mentions the conviction of Zhou Shifeng as indicating that the courts are doing their part to crack down on state subversion. It appears to be another in a series of colorless government reports. But for those with the ability (or at least the patience) to decode this report, it provides insights into the Chinese courts, economy, and society.

The report, which went through 34 drafts, is intended to send multiple signals to multiple institutions, particularly the political leadership, in the months before the 19th Party Congress.

According to a report on how the report was drafted, the drafting group (which communicated through a Wechat group to avoid time-consuming bureaucratic procedures) faced the issue of how to summarize the work of the People’s Court in 2016 correctly. The guidance from President Zhou on the report–it must:

- fully embody the upholding of Party leadership, that court functions (审判职) must serve the Party and country’s overall situation;

- embody the new spirit of reform, showing the (positive)impact of judicial reform on the courts and show the ordinary people what they have gained;

- not avoid the mention of problems, but indicate that they can be resolved through reform.

Underneath these political principles, the operation of a court system with Chinese characteristics is visible.

A partial decoding of the report reveals the points listed below (to be continued in Part 2).

1. Caseload on the rise

The caseload in the Chinese courts continues to rise significantly, at the same time that headcount in the courts is being reduced. Diversified dispute resolution (the jargon outside of China is alternative dispute resolution) is being stressed.

- SPC itself is dealing with a massive increase in its cases, 42.6% higher than 2016, and that number was significantly higher than 2015.

2016, SPC cases accepted 22,742, up 42.3%, concluded 20151, 42.6%, Circuit Cts #1 & 2 accepted 4721 cases in last 2 yrs, resolved 4573 cases

The statistics on the SPC’s caseload are not broken down further, but are understood to be mostly civil, commercial, and administrative. It appears from a search of one of the case databases that not all of the SPC judgments or rulings have been published (a search of one of the judgment databases showed 6600+, and only some of the death penalty approvals). It seems also that the database does not include SPC cases such as the judicial review of certain foreign and foreign-related arbitration awards.

Although the report does not focus on the reasons for the massive increase in SPC cases, careful observation reveals the following reasons:

- establishment of the circuit courts, hearing more cases and ruling on applications for retrials;

- increase in the number of civil and commercial cases with large amounts in dispute;

- SPC itself has implemented the case registration system; and

- changes in law giving litigants rights where none previously existed.

The report also mentioned that 29 judicial interpretations were issued (some analyzed on this blog) and that 21 guiding cases were issued. Model cases and judicial policy documents were not separately set out, although some were listed in the appendix to the SPC report distributed to delegates.

Lower courts

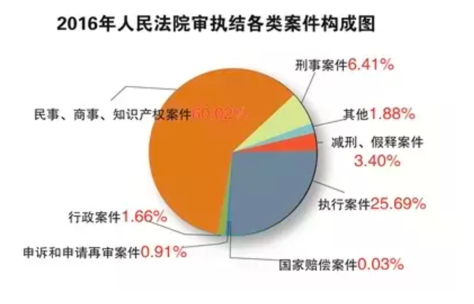

The pie chart below sets out the statistical distribution of cases heard by the Chinese courts:

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows:

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows:

- about 60% of those cases were civil, commercial, or intellectual property cases;

- 6.41% criminal cases,

- 3.40% parole, sentence reduction cases;

- almost 26% enforcement cases,

- .03% state compensation cases,

- petition or application for retrial, .91%;

- and 1.66% administrative cases.

Although the stress in Zhou Qiang’s report is placed on law and order, in fact many more cases in the Chinese courts are civil and commercial rather than criminal.

2. Social stability, public order, law & order are major concerns

Criminal cases have a prominent place in the report, although the data reveals a slight increase in the number of cases (1.5%), involving the conviction of 1,220,000 people, down 1%. (Note that many minor offenses are punished by the police, with no court procedures).

Although the report mentioned the Zhou Shifeng case (state security) and criminal punishment of terrorist and cult crimes, it did not release statistics on the number of cases of any of these crimes heard. Corruption cases totaled 45,000 cases, involving 63,000 persons. Violent crimes (murder, robbery, theft) cases 226,000. Drug cases: 118,000, a significant decrease from 2015. 2016 cases of human trafficking and sexual assault on women and children totaled 5335, while telecommunications fraud cases in 2016 totaled 1726. Only 213 cases involving schoolyard bullying were heard and the SPC revealed that the drafting of a judicial interpretation on the subject is underway. The report highlighted some of the well-known criminal cases, including the insider trading case against Xu Xiang and the Kuai Bo obscenity cases to illustrate and criminal law-related judicial interpretations to signal that the courts are serving policy needs in punishing crime.

The same section described what has been done in 2016 to correct mistaken cases, highlighting the Nie Shubin case (reheard by Judge Hu Yuteng and colleagues) as an example. The report revealed that the local courts retried only 1376 criminal petition cases, likely a tiny fraction of the criminal petitions submitted.

3. Maintain economic development

As President Zhou Qiang indicated, the way that the Chinese courts operate is Party/government policy-driven (they must serve the greater situation). Serving the greater situation meant, in 2016, that the Chinese courts heard 4,026,000 first instance commercial cases, a 20.3% increase year on year. He also mentioned the 3373 bankruptcy cases analyzed in an earlier blogpost. Of those 4 million commercial cases, 1,248,000 involved securities, futures, insurance, and commercial paper and 255,000 real estate cases and 318,000 rural land disputes. Other implications are discussed below.

This section of the report devoted a paragraph to a topic discussed last year on this blog: the courts serving major government strategies, including One Belt One Road, the Yangtze River Belt, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development.

Green development , intellectual property (IPR), property rights (of private entrepreneurs), serving maritime and major country strategy, socialist core values, judicial solutions to new problems and cross-border assistance also merited mention in this section.

- The courts heard 133,000 environmental and natural resources cases, with Fujian, Jiangxi and Guizhou courts designated as experimental environmental courts. While public interest environmental and procuratorate brought (environmental) cases were mentioned, statistics were not set out.

- First instance IPR cases totaled 147,000, with several cities (Nanjing, Suzhou, Wuhan, and Chengdu) establishing IPR divisions to take cases across administrative boundaries. This section mentioned the Jordan trademark case and the IPR courts.

- On protection of property rights, the report mentioned some of the documents intended to protect private entrepreneurs discussed on this blog, as well as 10 model cases.

- On maritime and cross-border cases, the report mentions the judicial interpretations on maritime jurisdiction (discussed in this blogpost), intended to support the government’s maritime policy, including in the South China Sea. The Chinese courts heard only 6899 commercial cases involving foreign parties (this means that of the 2016 19,200 civil and commercial cases mentioned by Judge Zhang Yongjian, most must have been civil) and 16,000 maritime cases. The report again mentions making China a maritime judicial center, further explained in my 2016 article.

- On the relevance of socialist core values to the courts, that is meant to incorporate socialist core values into law (although they should be understood to have always to be there) and to give the Langya Heroes special protection under China’s evolving defamation law.

- Judicial solutions to new issues included internet related issues, including e-commerce cases, internet finance cases, and theft of mobile data; the first surrogacy case, and judicial recommendations to Party and government organizations.

- In the section on international cooperation, President Zhou Qiang revealed that fewer than 3000 cases involving mutual judicial assistance were handled. The bureaucratic and lengthy procedures for judicial assistance in commercial cases has long been an issue for lawyers and other legal professional outside of China. This is likely to change (in the long run, as Chinese courts increasingly seek to obtain evidence from abroad). US-China dialogue on bankruptcy issues and cooperation with One Belt One Road countries (cases involving these countries are increasing significantly), were also mentioned here.

TO BE CONTINUED

The 6,900 maritime cases are a significant part of China’s foreign related docket (25,900 in 2016, according to your posting on foreign cases) – about one fourth. In fact if numbers drove politics, the foreign maritime docket would be a major focus of foreign engagement with China on its judiciary, rather than civil IP enforcement, which was about 1,327 in 2015, or about 1.2 percent of the IP docket, or about one fifth of the foreign maritime docket (see: https://chinaipr.com/2016/04/22/summarizing-the-spcs-2015-white-paper/). Comparisons between foreign maritime cases and foreign IP cases would be a useful subject for further study in order to better understand the reasons foreigners pursue foreign maritime cases so frequently and/or IP case so infrequently. Thanks again for another great posting.

I believe foreign parties are often defendants in maritime cases, although I would need to confirm this perception with friends in the maritime courts. I will have to give more thought to the maritime/IPR court comparison.