The nine presiding judges of the #2 Circuit Court are whom Chief Judge Hu Yunteng calls “The Nine.” It could be: 1) Judge Hu is a fan of the Jeffrey Toobin book on the (US) Supreme Court, which has a Chinese translation thanks to Judge He Fan; or 2)he wants others to know that he has some basic knowledge about the US Supreme Court. (For the avoidance of any doubt, this does not mean Judge Hu is looking to transport the US judicial system to China).

The role and utility of China’s circuit courts have moved into public focus with the establishment of four additional circuit courts (discussed earlier). Some have commented that they have been established just to divert petitioners from Beijing.An article published by a European think tank commented that the circuit courts weaken the power of local judges and courts in the provinces.

But when analyzing what Chinese courts do and how they operate, moving away from grand theory and into the specifics of what they do provides (to this foreign observer and I trust Chinese ones as well) more nuanced insights. It helps to understand better what the circuit courts are doing, how Chinese courts operate, how Chinese judges think, and what practical solutions Chinese judges evolve in the context of their political, legal and social environment. What exemplifies this is a report that the #2 Circuit Court did on petitioning appeals related to criminal cases (第二巡回法庭刑事申诉来访情况分析报告). The report concerns petitions for retrial made under the Criminal Procedure Law’s trial supervision procedure.

While the full report does not seem to be easily available, Chief Judge Hu Yunteng summarized some of what appear to be the main findings of the report in a June, 2016 interview with 中国审判 (China Trial), a SPC journal and Wechat account. The audience for China Trial is primarily his brother and sister judges, so his comments were relatively frank and the legal context about which he was speaking would be taken for granted. His comments, which I am summarizing below, reflect the insights of someone who lived through the Cultural Revolution, and has worked at the intersection of legal research and judicial practice for many years. (His Chinese profile is more complete than the English one).

He said that his remarks were drawn from his experience in hearing nearly 200 cases at the #2 Circuit Court, the majority of which were criminal petition cases (刑事申诉)(cases retried under trial supervision procedures). The cases, he said, reflect issues with criminal cases both at first instance or on appeal, as well issues all courts face coping with criminal petitions. Moreover, he said, the #2 Circuit Court (and SPC headquarters) have more and more petitioners seeking redress, plus an ever increasing backlog of cases. People have been petitioning for a little as 3-5 years, long as 10-18 years, or even 20-30 years, clocking over a hundred visits. Over 700 petitioners visited the #2 Circuit Court with grievances about the decisions of the Liaoning Higher People’s Court.

Judge Hu gave his views on why are there so many of these cases and what should be done.

Why so many cases?

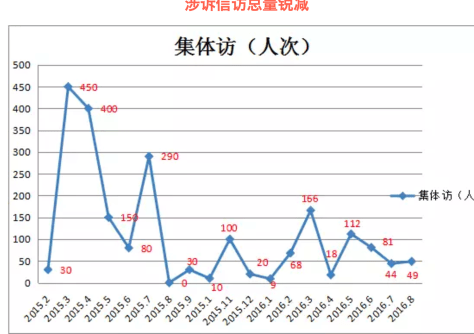

(Graph tracking petitioner visits to the #2 Circuit Court (not from the interview):

A summary of Judge Hu’s analysis follows below, with some comments in brackets.

Reasons for these cases

“The reasons are complicated.” He believed that the number of mistaken/unjust cases were small in number, and 90% of the petitioning cases involved cases decided properly, with 9% with some errors, but only 1% with errors serious enough for the case to be re-tried. The reasons, he believed, lay deeper.

- Defects in the criminal procedure system. It has a two instance system, with the second instance as final; time limits on hearing criminal cases; and criminal petitioning system. With societal change and ordinary people have greater legal consciousness and demands for justice. This criminal procedure system is incompatible with current societal demands (这些制度已经不能适应新时期的需要). In some areas of China, there are more petitions from second instance decisions than appeals.

Most jurisdictions, whether common law or continental (including Hong Kong and Macau) have a three-instance system, and if China does not change this and have a limited third instance system, the criminal case petitioning problem will not be solved. The strict time limits mean facts are not clarified, a good job is not done at trial, and case quality is not maintained, creating errors that causing petitioning. The lack of time limits on petitioning is a major reason that it exists. [Note: Judge Hu saying this does not mean the Chinese government will change its system immediately or in the near future. His voice is a powerful and persuasive voice identifying this as a core reason for so many petitions, but this must be understood within the context that he said it. This is his analysis, not a signal that the Chinese government will change its criminal justice system immediately.

Implementing a [limited] three-instance system is a major criminal justice policy change, with social stability, financial and personnel implications (as seen from the government’s perspective). Proposals to make such a fundamental change to criminal procedure law would come after a great deal of analysis and consultation with the authorities involved. Judge Hu does not elaborate on what he means by a limited third instance system, but research shows this concept is being explored by a variety of thinkers and scholarship on the topic dates back over 10 years. Those following Chinese criminal justice system reforms should be aware that the renown Professor Chen Guangzhong revealed (in an interview in June, 2016) that amendments to the Criminal Procedure Law are under consideration, although the details are not yet known. ]

2. Problems in judicial practice. There aren’t enough staff to hear the cases carefully, and cases are no longer limited to traditional crimes, with cases more complicated and evidence harder to assemble. More sophisticated defendants no longer passively accept the sloppy work being done by people handling these cases (办案人员)(referring to police/prosecutors/judges, as appropriate). It causes errors in: collection of evidence; forensics; determinations; incomplete compliance with legal procedures; inappropriate legal explanations; cases handled inappropriately. Moreover,the cases reflect problems in the way a significant proportion of those handling cases think about law: failure to correctly understand basic legal relationships such as fighting crime and protecting defendant’s rights; the relationship between public security, procuratorate, and courts; the relationship between handling criminal cases and resolving social conflicts, etc. All these things cause an increase in the number of petitioners. [Again, this his analysis reflecting his many years of experience and observation.]

3. Changes in the legal and social environment. These are another set of reasons for so many criminal petitioning cases.Judge Hu said, actually, the increase in criminal petitioning isn’t an entirely bad phenomenon. It is part of the process in improving the rule of law. The state respects human rights more and people are more aware of their rights and are increasingly daring to defend their rights.Moreover, societal public opinion has encouraged people after they have read in the media that mistaken/unjust cases have been corrected. Moreover, criminal punishment for the same offense has varied greatly, depending on whether it was during the “Strike Hard” or other campaigns, so when people look from today’s perspective at these cases, they feel it is unfair.

What to do about it?

Judges dealing with these cases need legal knowledge and political wisdom.

- Respect petitioners. Petitioning is a basic human right. Judges should not think that petitioners are making trouble from nothing. In the #2 Circuit Court Judge Hu requires judges receiving petitioners to be patient in explaining the law. So treating petitioners’ litigation rights seriously is a way to deal with them

- According to law, petitions should be submitted to the court that heard the case originally. The case filing or trial supervision departments of these courts should seriously review the cases, if there is an error, retry the case on the court’s own initiative. If the case lacks errors, the facts and law should be explained to the petitioning party. This is assuming responsibility to the facts, law, parties, and people.

- The higher courts need to do a better job of supervising the lower courts. Courts need to balance respect for effective judgments with a party’s petitioning rights. Courts should determine whether the issue is procedural or substantive. Cases can’t be rushed–some can be dealt with quickly and others not. Higher courts should take on more difficult and complicated cases themselves.

- Petitioning cases should be heard by three judge collegial panels, by reviewing the file and questioning persons if needed, questioning the party and if he (she) is in custody, summoning him for questioning, hearing the views of the party’s lawyer if one has been appointed and making contact with the party and his lawyer an important way to deal with these cases. Moreover, the lower courts should appoint more qualified and experienced people to handle criminal petitions, as it is often not currently the case.

- As some of these cases relate to a specific time period, sometimes it is necessary to work with the higher or lower courts, or seek support from the government or Party to deal the matter. For example, some cases were correctly decided at the time, but the decision is no longer appropriate under current circumstances. Retrial is not possible but coordination is possible through the implementing authorities [presumably the jail] or procuratorate.

Connection with judicial reform

Presumably Judge Hu’s report and analysis are part of a project connected with larger judicial reform issues. See Article 36 of the 4th Five Year Court Reform Plan:

36. Reform the system for petitioning involving litigation.Improve mechanisms for the separation of petitioning and litigation work, clarifying the standards, scope and procedures for separating litigation and petitioning. Create finality mechanisms for petitioning involving litigation, standardizing the sequence for petitioning involving litigation in accordance with law. Establish mechanisms for steering and receiving petitioners at their source, and innovation networks for handling petitioning. Promote the establishment of a system for lawyer representation of in complaint appeals cases. Explore the establishment of mechanisms for lawyers to participate as third-parties, increasing the diversity of joined forces for resolving conflicts in petitioning related to litigation.

Effect of these comments

Presumably Judge Hu has sought to implement some of his own recommendations, such as requiring his own judges to do a better job receiving petitioners, and expecting the lower courts to do the same. It is likely that Judge Hu has made his views known in meetings with judges from Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. So this appears to be one piece of evidence that the circuit courts are having an effect on the quality of justice delivered.

Since petitioners “vote with their feet,” it appears that one indicator would be a downturn in the number of petitioners with grievances about criminal cases in the Liaoning Courts. How his report and recommendations will be considered nationwide remains to be seen. As a member of the SPC’s judicial committee, his full report and more detailed recommendations are likely to have an impact on the thinking of SPC colleagues. As to the larger issues Judge Hu has raised, we are unlikely to see any immediate or short term impact because of the complex politics linked to those reforms.

Great post. Just wish to point out that strict time limits exist mainly because otherwise many (if not most) defendants would be detained for a significantly longer time, maybe years, when the case is pending. I personally don’t object to the abolition of most time limits if it could lead to better case quality, on the condition that most defendants are granted bail.

I am also curious as to what Judge Hu meant by “有限的三审制度” (a limited three-instance system). Is he thinking of a second discretionary appeal (which I don’t think is fundamentally different from the current system–correct me if I am wrong) or habeas petition?

Lastly, regarding actually establishing a three-instance system for criminal cases, a renowned jurist hinted (http://china.caixin.com/2016-06-23/100957970.html) that the next NPC will *probably* amend the Criminal Procedure Law again. We are already approaching the 5-year anniversary of the latest CPL amendment, so the timing is plausible. But whether overhauling (instead of just perfecting) the trial-level system (审级制度) will be on the 19th CCP Central Committee’s to-do list awaits to be seen; It’s certainly not among the current top priorities.