Most readers of this blog are unlikely to know that the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) publishes on its website responses to selected letters to President Zhou Qiang that make suggestions and give opinions. In a July 11 response, the SPC revealed that individual bankruptcy legislation is on its agenda. As I suggest below, actual legislation is likely to come later.

Most readers of this blog are unlikely to know that the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) publishes on its website responses to selected letters to President Zhou Qiang that make suggestions and give opinions. In a July 11 response, the SPC revealed that individual bankruptcy legislation is on its agenda. As I suggest below, actual legislation is likely to come later.

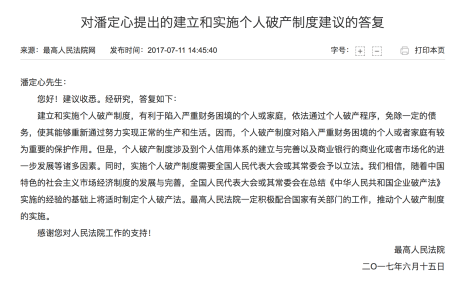

The letter said:

Dear Mr. Pan Dingxin:

We received your proposal, and after consideration, we respond as follows:

establishing and implementing an individual bankruptcy system is beneficial for those individuals or households who have fallen into serious financial distress to exempt some of their debts and enable them again through their hard work to achieve normal business and living conditions. Because of this, it has an important function to protect individuals and households that have fallen into financial difficulties. However an individual bankruptcy system relates to the establishment and improvement of an individual credit system and commercialization of commercial banks or their further marketization and other factors. At the same time, the implementation of an individual bankruptcy system requires the National People’s Congress or its Standing Committee to legislate. We believe that with development and improvement of the socialist market economic, the National People’s Congress or its Standing Committee will promulgate an individual bankruptcy law on the basis of the experience with the “PRC Enterprise Bankruptcy Law.” The Supreme People’s Court will definitely actively support the work of the relevant departments of the state, and promote the implementation of an individual bankruptcy system.

Thank you for your support of the work of the Supreme People’s Court!

Supreme People’s Court

June 15, 2017

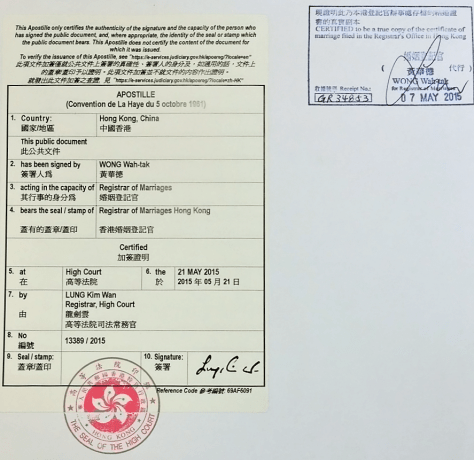

Few are aware that Shenzhen has been working on draft individual bankruptcy legislation for several years now, looking to Hong Kong’s experience and legislation, described in a recent report as a “complete” individual bankruptcy system (“完善的个人破产制度”). The process has been going on for so long that the team (designated by the local people’s congress and lawyers association) and headed by a Shenzhen law firm partner published a book one year ago with its proposed draft and explanations.

Few are aware that Shenzhen has been working on draft individual bankruptcy legislation for several years now, looking to Hong Kong’s experience and legislation, described in a recent report as a “complete” individual bankruptcy system (“完善的个人破产制度”). The process has been going on for so long that the team (designated by the local people’s congress and lawyers association) and headed by a Shenzhen law firm partner published a book one year ago with its proposed draft and explanations.

Although Professor Tian Feilong of Beihang University’s Law School has been recently widely quoted for his statement about Hong Kong’s legal system undergoing “nationalisation,” this is an example, known to those closer to the the world of practice, that Hong Kong’s legal system is also seen as a source of legal concepts and systems that can possibly be borrowed. The drafting team looked at Hong Kong (among other jurisdictions) and others in China have proposed the same as well.

Shenzhen’s municipal intermediate court has completed an (award-winning) study on judicial aspects of individual bankruptcy shared with the relevant judges at the SPC.

If recent practice is any guide, individual bankruptcy legislation will be piloted in Shenzhen and other regions before nationwide legislation is proposed, and it will be possible to observe the possible interaction between those rules and the government’s social credit system. So national individual bankruptcy legislation appears to be some years off.

As to why the SPC has a letter to the court president function, the answer is on the SPC website: it is to further develop the mass education and practice campaign (mentioned in this blogpost four years ago) and listen to the opinions and suggestions of all parts of society (the masses). Listening to the opinion and suggestions of society are also required of him as a senior Party leader, by recently updated regulations. The regulations are the latest expression of long-standing Party principles.

I recently published an

I recently published an

You must be logged in to post a comment.