In February, 2017, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued its second judicial transparency white paper, giving the official version of what the SPC has done to respond to public demands for greater transparency about the Chinese judicial system. But what are the voices from the world of practice saying? One of the issues (for a small but vocal group, foreign litigants) is inconsistent and non-transparent formalities requirements.

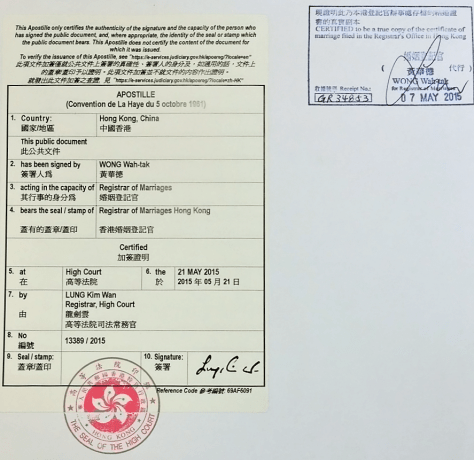

Chinese civil procedure legislation requires a foreign litigant to notarize and legalize corporate documents, powers of attorney & other documents. It is a time consuming and costly process, with some jurisdictions providing documents that do not meet the expectation of Chinese courts. China is not yet a signatory to the Hague Convention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents (Hague Legalization Convention) which substitutes the faster and cheaper apostille process (note that Hague Legalization Convention continues to be applicable to Hong Kong and Macau under the terms of the joint declarations and Basic Laws for each Special Administrative Region (SAR)). About one year ago, a Ministry of Justice official published a Wechat article discussing the benefits of the Hague Legalization Convention (as well as the issues facing China in implementing it).

While this article addresses issues faced by foreign plaintiffs seeking to challenge Trademark Review and Adjudication Board decisions in the Beijing Intellectual Property Court (Beijing IP Court), according to other practitioners (who have asked not to be identified), these problems with inconsistent (and non-transparent) requirements concerning legalizing foreign corporate documentation are not limited to the Beijing IP Court, but face foreign parties appealing from intermediate courts to provincial high courts elsewhere in China. These requirements can have the effect of cutting off a party’s ability to bring an appeal, for example.

What is the solution? The long-term solution, of course, is for China to become a signatory to the Hague Legalization Convention. In the meantime, Chinese courts should be more transparent about their formalities requirements. These requirements affect all foreign parties, whether they are from One Belt, One Road (OBOR) countries or not. If China is seeking to become an international maritime judicial center or hear more OBOR commercial cases, the Chinese courts need to become more user friendly. Courts with significant numbers of foreign cases (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen….) can consider reaching out to the foreign chambers of commerce, many of which have legal committees, to understand in greater detail what specific problems foreign litigants face (and convey their views to foreign audiences). Resolving this issue can create some goodwill with the foreign business community with relatively little effort.

One thought on “Chinese courts & formality requirements”