This blogpost continues the analysis in Part 1, which analyzed the first several sections of Zhou Qiang’s work report to the National People’s Congress, concerning court caseload, social stability and criminal punishment, and the courts serving to maintain the economy.

Most people who have commented (outside of China) on Supreme People’s Court (SPC) President Zhou Qiang’s March, 2017 report to the National People’s Congress (NPC) didn’t have the patience to read (or listen) much beyond the initial section, which mentions the conviction of Zhou Shifeng as indicating that the courts are doing their part to crack down on state subversion. It appears to be another in a series of colorless government reports. But for those with the ability (or at least the patience) to decode this report, it provides insights into the Chinese courts, economy, and society.

The report, which went through 34 drafts, is intended to send multiple signals to multiple institutions, particularly the political leadership, in the months before the 19th Party Congress.

According to a report on how the report was drafted, the drafting group (which communicated through a Wechat group to avoid time-consuming bureaucratic procedures) faced the issue of how to summarize the work of the People’s Court in 2016 correctly. The guidance from President Zhou on the report–it must:

- fully embody the upholding of Party leadership, that court functions (审判职) must serve the Party and country’s overall situation;

- embody the new spirit of reform, showing the (positive) impact of judicial reform on the courts and show the ordinary people what they have gained;

- not avoid the mention of problems, but indicate that they can be resolved through reform.

Underneath these political principles, the operation of a court system with Chinese characteristics is visible.

Guaranteeing people’s livelihood rights & interests

The following section is entitled “conscientiously implement people-centered development thinking, practically guarantee people’s livelihood rights and interests.” It summarizes what the courts have been doing in civil and administrative cases, but it also signals their perceived importance in this national report.

Civil cases

President Zhou Qiang noted that the Chinese courts heard 6,738,000 civil (民事) cases, an increase of 8.2%. Although he did not define what he meant by civil cases, under Chinese court practice, it refers to the type of cases under the jurisdiction of the #1 civil division (see this earlier blogpost):

- Real estate, property and construction;

- Family;

- Torts;

- Labor;

- Agriculture;

- Consumer protection; and

- Private lending.

On labor cases, the report mentioned that the courts heard 473,000 labor cases. This is a slight decrease from 2015 (483,311) (although the report did not do a year on year comparison). The report signalled that the SPC is working on policy with the labor authorities on transferring cases from labor mediation, labor arbitration, to the courts. This was signaled previously in the SPC’s policy document on diversified dispute resolution. Articles on both the SPC website and local court websites have signaled the increasing difficulty of labor disputes, and the increase in “mass disputes.”

As explained in this blogpost, labor service disputes, relate to an “independent contractor,” but more often a quasi-employment relationship, governed by the Contract Law and General Principles of Civil Law, under which the worker has minimal protections. This year’s report did not mention the number of labor service cases. In 2015, the Chinese courts heard 162,920 labor service cases, an increase of 38.69%.

There was no further breakdown on the number of other types of civil cases, such as private lending or real estate cases. For these statistics, we will need to await any further release of big data by the SPC. As blogposts in recent months indicate, private lending disputes are on the rise in economically advanced provinces and bankruptcy of real estate developers remains a concern.

This section also mentions criminal proceedings against illegal vaccine sellers, although the topic may be more appropriately be placed with the rest of the criminal matters, but likely because it is an issue that drew widespread public attention.

Family law

Echoing language in recent government pronouncements, the section heading mentions protecting marriage and family harmony and stability. The report mentions that the courts heard 1,752,000 family law cases in 2016, with no year on year comparison with 2015. The report mentions that the SPC has established pilot family courts (as previously flagged on this blog).

Administrative disputes

First instance administrative disputes totaled 225,000 cases, a 13.2% increase over 2015, but a tiny percentage of cases in the Chinese courts. The report highlights developments in Beijing and Shanghai (they are being implemented in Shenzhen, although not mentioned), to give one local court jurisdiction over administrative cases. According to the statistics (in Beijing, at least), this has led to a sizeable increase in administrative cases. The report also mentions the positive role that the courts can play in resolving condemnation disputes (this blogpost looked at problems in Liaoning).

Hong Kong/Macao/Overseas Chinese cases

As mentioned by Judge Zhang Yongjian, the report mentions that the courts heard 19,000 Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Overseas Chinese related cases, and handled 11,000 judicial assistance matters with the three greater China jurisdictions. The report also mentions the recently signed arrangement between the SPC and Hong Kong judiciary on the mutual taking of evidence, a development that seems to have escaped the notice of the Hong Kong legal community.

Military related disputes

Unusually, the report mentioned that the local courts heard 1678 military-related cases and have developed systems for coordination between the civilian and military courts. These developments have been analyzed further in a blogpost on the Global Military Justice Reform blog.

Strictly governing the courts and institutional oversight

The following two sections of the report give a report on how the courts are upholding Party leadership, increasing Party construction within the courts, internal Party political life, and political study, all of which are in line with recent developments. Although these are stressed, this does not mean that professional competence is less valued. The increasing caseload, higher expectations of litigants, particularly in commercial cases, and increasing technical complexity of cases means that the SPC is in fact taking measures to improving professional capacity of the courts. This section also mentions courts and individual judges that have been praised by central authorities and 36 judges who have died of overwork.

On anti-corruption in the courts, the report mentions that 769 senior court officials have been held responsible for ineffective leadership, 220 have been punished for violations of the Party’s Eight Point Regulations. The SPC itself had 13 persons punished for violations of law and Party discipline (offenses unstated), 656 court officials were punished for abusing their authority, among whom 86 had their cases transferred to the procuratorate.

On institutional oversight, the report signals that the SPC actively accepts supervision by the NPC, provides them with reports, deals with their proposals, and invites them to trials and other court functions. On supervision by the procuratorate, the report revealed that the SPC and Supreme People’s Procuratorate are working on regulations on procuratorate supervision of civil and enforcement cases, a procedure sometimes abused by litigants.

2016 and 2017 judicial reforms

2016

On 2016 judicial reform accomplishments, the following were highlighted:

- circuit courts;

- case filing system;

- diverse dispute resolution;

- judicial responsibility;

- trial-centered criminal procedure system;

- separation of simple from complicated cases;

- people’s assessors‘ reform;

- greater judicial openness;

- more convenient courts;

- improving enforcement (enforcement cases were up 31.6% year on year), including using the social credit system to punish judgment debtors.

2017

The report mentions that among the targets for the courts is creating a good legal environment for the successful upcoming 19th Party Congress. That is to be done through the following broad principles:

- using court functions to maintain stability and to promote development (for the most part mentioning the topics reviewed earlier in the report);

- better satisfying ordinary people’s demands for justice;

- implementing judicial reforms, especially those designated by the Party Center;

- creating “Smart” courts; and

- administering the courts strictly and improving judicial quality.

This last section mentions implementing recommendations required by the recent Central Inspection Group’s (CIG) inspection and Central policies applicable to all political-legal officials, before focusing on the importance of more professional courts, and improving the quality of courts in poor and national minority areas.

A few comments

It is clear from the above summary that the content of President Zhou Qiang’s report to the NPC is oriented to the upcoming 19th Party Congress and the latest Party policies. It appears that no new major judicial reform initiative will be announced this year.

It is likely too, that the selective release of 2016 judicial statistics in the NPC report also relates to messaging in line with the upcoming 19th Party Congress, although we know that the SPC intends to make better use of big data. We can see that overall, the caseload of the courts is increasing rapidly, including institutionally difficult cases (such as bankruptcy and land condemnation), which put judges and courts under pressure from local officials and affected litigants. In the busiest courts, such as in Shanghai’s Pudong District, judges will be working extremely long hours to keep up with their caseload, and the impact of new legal developments. It appears (from both the report and the results of the CIG inspection) that judges will need to allocate more time to political study. How this will play out remains to be seen. We may see a continuing brain drain from the courts, as we have seen in recent years.

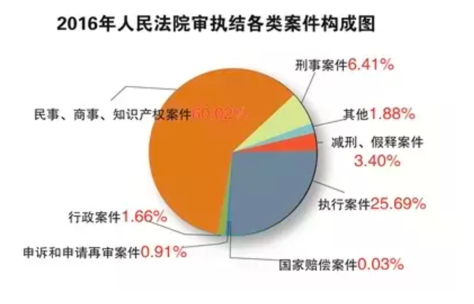

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows:

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows:

You must be logged in to post a comment.