Supreme People’s Court (SPC) President Zhou Qiang has been widely quoted for saying in January of this year that Chinese courts should strengthen ideological work and show the sword to mistaken Western ideas of “constitutional democracy”, “separation of powers” and “judicial independence.” What is not widely known outside China is that the relationship between the Chinese judiciary and some of the major international judiciaries (I’ll use the term “Western”) is more nuanced than it appears. Close observation reveals the following:

- high-level summits between major foreign and Chinese judiciaries;

- senior Western judges speaking to or providing training to senior Chinese judges;

- pilot projects in the Chinese courts involving foreign judiciaries;

- SPC journals and media outlets publishing the translation of cases from and reports of major Western judiciaries; and

- SPC judges reviewing legislation, institutions, and concepts from other judiciaries in judicial reform.

The official position on borrowing/referring to foreign legal models is set out in the 4th Plenum Decision (as I wrote earlier):

Draw from the quintessence of Chinese legal culture, learn from beneficial experiences in rule of law abroad, but we can absolutely not indiscriminately copy foreign rule of law concepts and models.

President Xi Jinping further elaborated this view on his visit to China University of Political Science and Law on May 3:

China shall actively absorb and refer to successful legal practices worldwide, but they must be filtered, they must be selectively absorbed and transformed, they may not be swallowed whole and copied (对世界上的优秀法治文明成果,要积极吸收借鉴,也要加以甄别,有选择地吸收和转化,不能囫囵吞枣、照搬照抄).

[The Xinhua report on Xi’s visit in English–“China should take successful legal practices worldwide as reference, but not simply copy them” omits the detail found in the Chinese reports.

Some examples of the way the SPC considers the “beneficial legal experiences in the rule of law abroad”:

- High level summits (some of which were agreed to on a presidential/head of state level) on commercial legal issues, such as the August, 2016 U.S.-China (or China-U.S.) Judicial Summit

“Our three talented and experienced U.S. judges discussed with senior Chinese judges and other experts topics relevant to commercial cases, ranging from case management to evidence, expert witnesses, amicus briefs, the use of precedents and China’s system of “guiding cases.” Speakers from both sides gave presentations that explored complex questions on technical areas of law. The conversations, during the formal meetings and tea breaks, were lively, candid, direct and constructive, highlighting both the similarities in and important differences between the U.S. and Chinese legal and judicial systems. I told our Chinese hosts that the views our judges expressed would be entirely their own, reflecting our separation of powers and the independence of our judiciary. Our judges displayed that independence as they weighed in on a range of issues, such as the role of precedents in interpreting statutes and the challenge of balancing public access to information while safeguarding privacy and protecting trade secrets.

Several of the Chinese participants discussed pending cases in U.S. courts involving Chinese defendants. I [William Baer] believe it was useful for us to air our differences and for our experts to exchange views on technical and sensitive areas of law. At the meeting, it was clear that although we come from different backgrounds and will not always agree, we all recognize the importance of legal reasoning and that increased transparency is a way of earning the public’s trust in the fairness and objectivity of the judicial system.”(from the DOJ website).

2. Training of Chinese judges by foreign judges

A number of foreign judiciaries have in place long-term training programs with the Chinese judiciary, with the German judiciary among the pioneers. The National Judicial College (NJC) (affiliated with the SPC) has a long-term program in place with the Germany judiciary, involving the German Judicial Academy, the German Federal Ministry of Justice & Consumer Protection, GIZ (the German international cooperation organization) and other parties, which teaches subsumption and related techniques of applying laws to facts (further explained here). The NJC has published a set of textbooks that apply the subsumption method to Chinese law.

It is likely that close to 10,000 Chinese judges have been trained under the German program. Common sense indicates that the NJC has continued with the program because it is useful to Chinese judges.

A recent example of the German training program is illustrated by the photo above, showing Dr. Matthias Keller, presiding judge of the Aachen administrative court giving a training course on the methodology of the application of law in administrative law to 150 Chinese administrative judges, mostly from intermediate and higher people’s courts.

3. Pilot projects in the Chinese courts involving foreign judiciaries

Australian judges have worked with the Australian Human Rights Commission on a ‘Sino-Australia Anti-Domestic Violence Multi-Agency Putian Pilot Program’ in Putian, Fujian Province, involving judges from the SPC, Fujian Higher People’s Court, and Putian Intermediate Court.

4. Publishing the translation of cases and reports from foreign judiciaries.

Some examples in recent months include:

- excerpts from Supreme Court decision Padilla v. Kentucky (published 7 February 2017), for those unfamiliar, it relates to plea bargaining and effective counsel);

- U.S. Chief Justice Robert’s 2016 year end report on the federal judiciary;

- U.S. federal judiciary’s strategic plan, for their takeaways for a Chinese audience;

- Summary of a July, 2016 report on cameras in the federal courts;

- Summary of the UK’s 2015 Civil Justice Council’s Online Dispute Resolution Advisory Group’s report on Online Dispute Resolution for Low Value Civil Claims.

5. Considering foreign legal concepts in judicial reform

Foreign legal concepts are considered by the SPC in a broad range of areas of legal reform, most of them unknown to foreign observers. Several of the more well known examples include: plea bargaining (see this article by an SPC judge (a comparison with the US “model” is included in Jeremy Daum’s analysis of China’s expedited criminal procedure reform). Last year’s policy document on diversified dispute resolution (previous blogpost here) specifically mentions considering concepts from abroad,On the ongoing amendments to the Judges’ Law (the draft has not yet been released), SPC Vice President Shen Deyong said in late April, “we need to learn from and refer to the successful practices of the management system of the judicial team by jurisdictions abroad, but they must be selectively filtered for Chinese use (要学习借鉴域外法官队伍管理的制度成果,甄别吸收,为我所用)。

Comment

A careful review of official statements, publications, and actions by the SPC and its affiliated institutions, as well as research by individual SPC judges shows an intense interest in how the rest of the world deals with some of the challenges facing the Chinese judiciary coupled with a recognition that any possible foreign model or provision will need to fit the political, cultural, economic, and institutional reality of China, and that certain poisonous ideas must not be transplanted. [Those particularly interested could pore through two publications of the SPC judicial reform office (Guide to the Opinions on Comprehensively Deepening Reforms of People’s Courts and the Guide to the Opinions on Judicial Accountability System of People’s Courts, in which the authors discuss relevant provisions in principal jurisdictions abroad.]

Those who either are most concerned about diluting the Chinese essence of the SPC (or jealous/emotionally bruised) seem to have saved their most poisonous criticism for off-line comments, as I am unable to locate a written version of the nasty comments that a senior Chinese academic shared with me about the over-Westernization of judicial reform or other nasty comments said to have been made about research by certain SPC judges into foreign legal systems. It is hard to know whether the persons involved are motivated by jealousy or a real belief that these measures described above will have a negative effect on the development of the Chinese judiciary. It seems safe to say that the concerns raised in the 19th century on the dilution of the essence of Chinese culture when borrowing from the West seem to be alive and well in the 21st century.

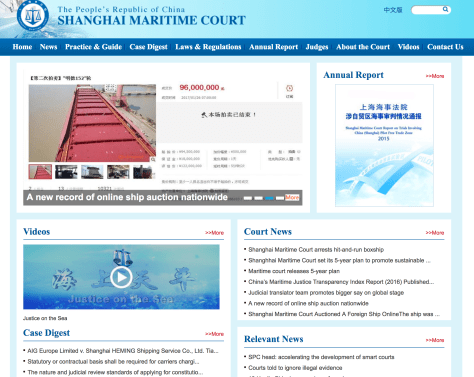

The Shanghai maritime court’s bilingual white paper for 2014 and 2015 is downloadable in PDF (under the Annual Report tab), the Court News is relatively timely, The case digests are useful and calendar lists upcoming court hearings (however without information concerning how an interested person could attend them). Unusually for a Chinese court website, the Judges tab has photos of judges other than the senior leadership. The Contact Us tab (unusual for a Chinese court) has only telephone numbers for the court and affiliated tribunals, rather than an email (or Wechat account). Of course the information on the Chinese side of the website is more detailed (under the white paper tab, for example, a detailed analysis of annual judicial statistics can be found), and the laws & regulations tab might usefully set out maritime-related judicial interpretations, but most of the information is well organized and relevant. Similar comments can be made about the Guangzhou maritime court’s website (

The Shanghai maritime court’s bilingual white paper for 2014 and 2015 is downloadable in PDF (under the Annual Report tab), the Court News is relatively timely, The case digests are useful and calendar lists upcoming court hearings (however without information concerning how an interested person could attend them). Unusually for a Chinese court website, the Judges tab has photos of judges other than the senior leadership. The Contact Us tab (unusual for a Chinese court) has only telephone numbers for the court and affiliated tribunals, rather than an email (or Wechat account). Of course the information on the Chinese side of the website is more detailed (under the white paper tab, for example, a detailed analysis of annual judicial statistics can be found), and the laws & regulations tab might usefully set out maritime-related judicial interpretations, but most of the information is well organized and relevant. Similar comments can be made about the Guangzhou maritime court’s website (

You must be logged in to post a comment.