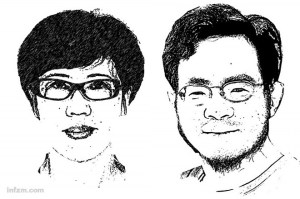

On 7 January 2022, Dean of Tongji University’s School of Law and Professor Jiang Huiling gave a guest lecture in my School of Transnational Law class. We were honored to hear Dean Jiang provide his unique perspective and insights on over 20 years of Chinese judicial reform and his insights on future developments. He has been involved with Chinese judicial reform starting from the first plan in 1999 (see also more about his background here). This blogpost summarizes his presentation. I have inserted my occasional comments in italics. If a point is not more fully elaborated, it means he did not do so.

On 7 January 2022, Dean of Tongji University’s School of Law and Professor Jiang Huiling gave a guest lecture in my School of Transnational Law class. We were honored to hear Dean Jiang provide his unique perspective and insights on over 20 years of Chinese judicial reform and his insights on future developments. He has been involved with Chinese judicial reform starting from the first plan in 1999 (see also more about his background here). This blogpost summarizes his presentation. I have inserted my occasional comments in italics. If a point is not more fully elaborated, it means he did not do so.

He spoke on the following six topics:

1. Brief History of Chinese Judicial Reform

2. How Judicial Reform Actions Are Taken

3. From the 4th to the 5th Judicial Reform Plan

4. Strategic Move: From Judicial Reform to “Zhengfa” (政法) Reform

5. Technical Measures: Rule of Law

6. Future Direction

1. Brief History

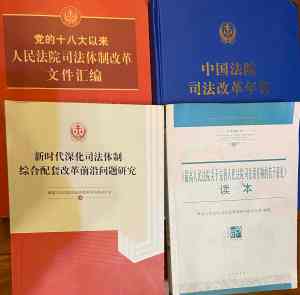

Dean Jiang went briskly through the history of judicial reform, commenting that in the first judicial reform plan, the focus was on raising public and professional awareness about the judiciary。 The second one, in which the Central Government greatly supported the SPC to undertake work mechanism (工作机制) reforms, not touching on structural reforms such as the status of judicial personnel. He noted that there was great progress during the second judicial reform plan. He called the third judicial reform plan a test before the New Era, and said that a decision had been taken to de-localize the judiciary and change the status of the judges and prosecutors, but at the end, there wasn’t internal confidence that the legal profession and society would accept such changes. He called the fourth judicial reform plan a structural, systematic, and radical change to the judicial system, especially the decision that judges would not be treated as ordinary civil servants. Dean Jiang characterized the fifth judicial reform plan as comprehensive and supplementary, and part of the Zhengfa reforms (as he further explained in the latter part of his presentation).

What were the lessons learned?

- Right (科学) concept of the judicial system (universal and with Chinese characteristics)–that the legal profession and the leading party accepted the value of the rule of law and the importance of the judiciary;

- Theoretical preparation–although he thought scholars had not done enough;

- Consensus for change–the judiciary is regarded as and is a bureaucracy–there is that consensus among both court leaders, who are legal professionals and with a Party role, and ordinary judges, who are legal professionals;

- Common achievements of human civilization–that means learning from other countries–China had done so not only in science and technology but also in law and democracy. Chinese judicial reformers had benefited from the open policy–he himself was an example; and

- Critical role of strong leadership–legal professionals could not initiate fundamental changes themselves–it needed court and political leadership to do so–he quoted General Secretary Xi Jinping on the ability to do what could not have been done before.

2. How Judicial Reform Actions are Taken

Dean Jiang rapidly made the following six points:

- Judicial awareness and enlightenment;

- Negative case matters;

- Reform for branches and reform for all (parochialism);

- Top-down design and comprehensive reform–the court system is part of the political system and reform has to be done by the Central Government;

- Coordination with other departments–in China, unlike in other countries, some matters require coordination with other departments, such as the Ministry of Finance;

- A group of devoted experts–both within the judiciary and among academics.

3. From the 4th to the 5th Judicial Reform Plan

Dean Jiang mentioned that the two plans are connected, but that significant differences exist in the value or orientation of the two plans. The fourth one made radical (revolutionary) changes to the judicial system. The fifth one is a new phase, and comes after the completion of the fourth one, which made the following fundamental changes:

- Structural changes–delocalizing the judicial system

- Status of the judges and prosecutors

- Changes to the internal operation of the judiciary

- Improvements to the guarantees for judges and prosecutors.

Although these reforms are not completed, these were the focus of their work in the judicial reform office of the SPC and of the Central Government.

The 4th judicial reform plan focused on the following:

1. Separation of administrative region and judicial jurisdiction area–delocalization, as Xi Jinping said, the judicial power is a central power, uniform application of law, so that the law is not applied in favor of one locality;

2. Judiciary-centered litigation system–“in the real world in China, the judiciary does not always have the final say”–and in the past the public security and prosecutors had the final say rather than the judges. The reform to have personnel and financing of courts at the provincial level is part of this reform;

3. Optimization of internal power allocation–as a court is a bureaucracy with different entities with different functions, and the leaders have different functions from ordinary judges;

4. Operation of hearing and adjudicatory power

5. Judicial transparency;

6. Judicial personnel–this is basic but very important; and

7. Independence of the court–this is basic but very important.

The 5th judicial reform plan:

- Party’s leadership

- Work for the country’s overall task and situation—subject of one of my forthcoming articles

- Litigation service–treat litigants properly and give them judicial services– the courts have public funds to pay for legal representation if people do not meet the standard for legal aid

- Judicial transparency–“always on the way”

- Responsibility-based judicial operation

- Court’s organization and function–reforms in that area (he referred to the recent repositioning of the four levels of the court system, among others)

- Procedural system

- Enforcement reform

- Court personnel system reform–better training of judges

- Smart court–using technology

The bolding above reflects his stress on those points in his presentation.

Dean Jiang mentioned that the Central Government put the court system into a bigger picture, but that the prior reforms were needed to make the judicial system more professional. It is for this reason that the Central Government mentions the phrase “judicial reform” much less than before.

The bigger picture is involving the court system more in the development of the whole country. This reflects a change in China’s overall policy, and we Chinese legal professionals need to understand this.

Comparing the 4th and 5th Reform Plans:

- Similar, but different;

- Duplicated, but deepening and supplementary;

- To those unfinished tasks, less emphasis

He said these should be seen in the context of the national plan for achieving the rule of law, and from 2035, China will have achieved rule of law and be a modernized, democratic country–the second 15-year plan will be about rule of law. He thinks that the timing is insufficient.

4. Strategic Move: From Judicial Reform to “Zhengfa” (政法) Reform

1. Before 2012, judicial work mechanism reform

2. From 2013,Judicial system reform

3. From 2017,Comprehensive supplementary reform of the judicial system

4. From 2019, Promoting Comprehensive

Reform in Zhengfa Area

5. From 2020,Xi Jinping rule of law thoughts

On point 4 above, that relates to a comprehensive document adopted in 2019 [Implementing Opinion On the Comprehensive Deepening Reforms of the Political-Legal Sector 关于政法领域全面深化改革的实施意见, not publicly available but mentioned previously on this blog], of which judicial reform plays only a small part. From 2020, Xi Jinping rule of law thoughts plays an important guiding role in the role of law. He said all law students and legal professionals should read it because it will have an important impact on the building of rule of law in China.

Structure of the new arrangement:

- Breadth: From the judiciary to other related areas

- Depth: From judicial system reform to broader systematic innovation–the latter means is moving from judicial system reform to areas previously little discussed, such as Party leadership and the role of the Political-Legal Commission, and the relationship between the Party and the law.

- Goal: From fair, efficient, and authoritative judicial system to modernization of Zhengfa work system and capability—that is, that the judicial system is to be part of a modernized governance system and governance capability [国家治理体系和治理能力现代化–from the Decision of the 4th Plenum of the 19th Party Congress]. That is the goal for the next 30 years. It means the rule of law in the future will have a major part to play as part of modernized governance, and the courts will have an even more important role to play in supporting this modernized state governance (this is in my draft article). It may not be apparent from the English words, but it is a change.

- Method: From branch-driven to Central Committee-driven–how to get there? He says this wording is not quite accurate as the 4th Judicial Reform Plan was also Central Committee driven, but because the Central Government put the project of the rule of law into the modernization of state governance, it has a different method for treating reform in the legal area, but he thinks that change of method is only an improvement.

- Nature: Chinese style and self-owned brand–when you read English language literature on building a fair and independent judicial system from abroad you will see many common points. In the current arrangement–in the Zhengfa reforms, Chinese characteristics have a great deal of weight and also in the reconstruction of the legal system. Although China has learned a great deal from other countries, China has to go on its own way, since it has its own history, political situation and historical stage and there is a change in the international situation. China has changed its position in the world. He is getting accustomed to this new way of judicial reform and it will be more difficult for foreigners to understand it.

The change of emphasis can be seen from the VIP (very important research projects of 2021), which are all more general than before:

No. 67. Practice and Experiences of the Party Comprehensively Promote Law-based governance

No. 68. Socialist Legal Theory with Chinese Characteristics

No. 69. Spirit of Socialist Rule of Law

No. 70. Constitution-centered Socialist Legal System with Chinese Characteristics

No. 71. Promoting Comprehensive

Reform in Zhengfa Area

Dean Jiang described the 2019 document mentioned above as containing the following areas of reform.

Seven Areas of Zhengfa Reform:

- Party’s leadership of the Zhengfa work–that is the Chinese situation

- Deepening reforms of Zhengfa institutions–not only the courts and the prosecutors, but changing the overall structure of Zhengfa institutions

- Deepening reform of systems of law implementation–we combined Legislative Affairs Office (of the State Council 法制办) into the Ministry of Justice [MOJ]–that’s an important change

- Deepening reform of social governance system–the Zhengfa Wei important for social governance–one of the most popular words is “governance“–how to support social stability, social development; innovative spirit, people’s lives;

- Public Zhengfa service system–public legal service is part of Zhengfa service–all the political-legal organs will work together to provide efficient high-quality services for the people-人民为中心–Xi Jinping says all our work needs to be people-centered;

- Zhengfa profession management reform–no major change here

- Application of IT technology–no major change here–continued application of IT in the Zhengfa area

These are seven areas of Zhengfa reform, based on the prior judicial reforms, but now going to a new stage. Governance is a crucial word.

5. Technical Measures

This is what he has devoted his life to before.

- Law is a profession, and the judicial system is the carrier of law and justice.

- Law is also science of law.

- Rule of law is one of the most technical way of state governance.

- Rule of law will have no efficacy without the joint efforts of other institutions.

He listed 10 legal issues for consideration for reference and research, as these are the most important topics:

- Structural reform: local judicial power, or central judicial power–at the present time, the Central Government cannot manage all those 200,000+ judges and prosecutors, and at first stage, the provincial level is taking that over, but he is not sure of the final judicial model

- Organizational reform: bureaucratic or judicial, especially the internal organs–this is a more technical reform, including internal and external organs, different tiers of the court and branches of the judiciary, including the procuracy;

- Functions of the four tiers of court: their role and function–cylinder, or cone (his metaphor of 20 years ago)–should the SPC concentrate on judicial interpretations and a small number of cases, and does not need 400 judges–this relates to the pilot program of late last year on the repositioning of the four levels of the Chinese court; the local courts will focus on factual issues;

- Personnel reform: Profession, or ordinary public servant–this is still an ongoing issue, and in his view, some continental European countries have not resolved this issue either. Although there are improvements, judges and prosecutors feel that it is not sufficient, given their new role in society, and the importance of their work. He agrees, having been a former judge.

- Procedural reform: Court-centered litigation system, fair trial, simplification of procedure–how to make things fairer, and given the more than 10% annual increase in cases, a big burden on judges in particular, how to simplify procedure. This links to the recent amendments to the Civil Procedure Law, which focuses on simplification of procedures and giving online procedures the same status as offline.

- Adjudication committee: advisory, or adjudication–there is a great deal of discussion about it–it is the highest decision-making body in a court (see this blogpost).

- Judicial responsibility system: The hearing officer makes the decision, and decision-maker takes the responsibility–司法责任制–this is another tricky one–this is required by the Central Government, a step forward towards the rule of law, instead of having a judge’s boss approve his decision (because the court is bureaucracy)–for China, this is a step towards the rule of law, but there is still a long way to go.

- Supervision over “four types of cases”–that means for most cases, judges take responsibility for their cases, but for difficult, controversial, and possibly having an impact on social stability–because junior judges have different capacities from the more senior–for those four types of cases, the court president and senior court leaders are involved to oversee or supervise (see translation of guidance here, commentary to come)–he has not found useful academic papers on this point;

- ADR (Diversified dispute resolution): this is a traditional topic–optimizing the allocation of resources of dispute resolution

- Judicial administration: local government loses its administrative power, but what internal administration;

- Judicial democracy: lay judge system–different from common law jury (but China can learn from the common law jury–having them focus on factual rather legal issues)–the law has changed, but academic work is insufficient.

- Judicial transparency–this is an old issue, to make the judiciary more transparent to the parties and the public.

These are the major issues in the next five years. These technical legal issues are very interesting and need legal scholars to look at them to support the Zhengfa reforms.

6. Future Direction

- Xi Jinping rule of law thoughts–inevitable guideline–some of political and strategic, but it provides some guidelines for basic principles;

- Rule of law-driven first;

- Politics driven and guarantee–politics should be a consideration but it should not be unbalanced. Political role of the rule of law-leading the legislative institutions. Guarantee means guaranteeing the executive implementation of law, supporting the judiciary, and being a model of a law-abiding citizen; This will be very important in putting judicial reform forward;

- To complete those halfway reforms–judicial personnel reforms;

- More rethought and theoretical guide–scholars criticize the judiciary for having an insufficient theoretical basis;

- Dealing with the other judicial civilizations–we never stopped, especially in technical areas, and for our legal professionals, that has never stopped. We need to work together for all of humanity.

On 7 January 2022, Dean of Tongji University’s School of Law and Professor Jiang Huiling gave a guest lecture in my School of Transnational Law class. We were honored to hear Dean Jiang provide his unique perspective and insights on over 20 years of Chinese judicial reform and his insights on future developments. He has been involved with Chinese judicial reform starting from the first plan in 1999 (see also

On 7 January 2022, Dean of Tongji University’s School of Law and Professor Jiang Huiling gave a guest lecture in my School of Transnational Law class. We were honored to hear Dean Jiang provide his unique perspective and insights on over 20 years of Chinese judicial reform and his insights on future developments. He has been involved with Chinese judicial reform starting from the first plan in 1999 (see also

You must be logged in to post a comment.