A recent message in the WeChat public account of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC)’s Administrative Division was devoted to promoting its new book, Supreme People’s Court Administrative Litigation User’s Guide (Administrative Litigation User’s Guide (2nd edition), 最高人民法院行政诉讼实用手册), shown in the photo above. Had the SPC’s #4 Civil Division had a WeChat public account last year when they published 涉外涉港澳台民商事审判业务手册( Foreign-Related, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan Related Commercial Trial Work Guide — “Foreign-Related Judicial Handbook”), I am sure that I would have received a similar message. I had previously thought that judicial handbooks were a historical artifact of the days before electronic databases. In my 1993 article, I discussed the phenomenon of judicial handbooks:

A recent message in the WeChat public account of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC)’s Administrative Division was devoted to promoting its new book, Supreme People’s Court Administrative Litigation User’s Guide (Administrative Litigation User’s Guide (2nd edition), 最高人民法院行政诉讼实用手册), shown in the photo above. Had the SPC’s #4 Civil Division had a WeChat public account last year when they published 涉外涉港澳台民商事审判业务手册( Foreign-Related, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan Related Commercial Trial Work Guide — “Foreign-Related Judicial Handbook”), I am sure that I would have received a similar message. I had previously thought that judicial handbooks were a historical artifact of the days before electronic databases. In my 1993 article, I discussed the phenomenon of judicial handbooks:

..A …problem is presented when the lack of consistency in issuance and authority makes it difficult for the lower courts to know when an interpretation is no longer valid…The [SPC] tries to cure these problems by issuing handbooks for adjudication in various subject areas….The Research Office and other divisions of the Court compile adjudication handbooks such as Sifa Shouce [司法手册] (Judicial Handbook), many of which are internal publications.

Some of those historical handbooks can be found in my research library of Supreme People’s Court publications–see here and below:

Why would specific divisions of the SPC return to the practice of issuing judicial handbooks in printed form? How does it link with the role of the SPC? What sources have the editors included, and what could students, scholars, and practitioners learn from that?

Official reasons for publishing these print books

The authors of the Administrative Litigation User’s Guide describe the reasons for publishing the book as follows:

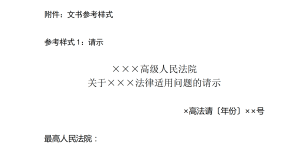

the Supreme People’s Court, on the one hand, provides professional guidance (业务指导) by formulating judicial policies 司法政策), issuing guiding cases, and making judicial replies (司法答复); on the other hand, it strengthens research and collects problems, and formulates judicial interpretations based on the accumulation and maturity of judicial practice. At present, the comprehensive judicial interpretation of the Administrative Litigation Law, the judicial interpretation of administrative agreements, and the judicial interpretation of the appearance of administrative agency heads in court to respond to lawsuits have been formulated and issued…, and there are more and more normative documents and guiding cases related to administrative litigation. In addition, with the increase in the number of administrative cases, more judges have joined the administrative trial team. In the process of gradually becoming familiar with administrative litigation, they urgently need to master the relevant provisions that have been issued and learn the relevant guiding cases. However, judicial replies are internal in nature, with a large volume and lack of a unified release mechanism. The channels for obtaining them from the outside world are limited, which is time-consuming and laborious.

According to the announcement, the audience for the Administrative Litigation User’s Guide is staff in administrative agencies, judicial practitioners, and researchers of administrative law [students and academics]. The editors note that to provide readers with reference materials and to make the book more practical, they have included guiding cases, SPC Gazette Cases, and typical cases from the last 10 years.

The #4 Civil Division authors/editors say their handbook is urgently needed by front-line judges and as a reference book for judges, arbitrators, lawyers, and other practitioners, and, I would add, to students and scholars seeking to decode the foreign-related and Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan-related operations of China’s judiciary.

Legal basis for publishing these books

Publishing these books is linked to Article 10 of the Organic Law of the People’s Courts and related documents, which authorize the SPC to supervise and guide(监督指导) the lower courts.

Comments on the content

Both books contain judicial interpretations and a range of SPC guidance documents such as meeting minutes/conference summaries (会议纪要), notices, and replies to requests for instructions, signaling to the reader that they are important sources of reference for judges and that “soft law” may understate the way that meeting minutes are understood within the Chinese court system.

The authors/editors of the Foreign-Related Handbook included many other types of legal provisions they considered relevant for hearing cross-border cases, such as relevant national legislation, administrative regulations, such as foreign exchange regulations, Chinese versions of international commercial rules (Incoterms, ICC Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees (URDG 758), ISP 98) ), Hague Conventions to which China has acceeded, and civil judicial assistance treaties, as well as some of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee decisions related to some of the international conventions. The #4 Civil Division did not include guiding, typical cases, and other types of cases it issues for reference. In my view, it was a practical decision that does not imply that those types of cases are irrelevant to judges hearing cross-border commercial cases, but rather that including cases would make the book too long to be published as a single volume.

Comment

The underlying rationale for publishing these judicial handbooks has not changed much in the past 30 years. Judges responsible for processing cases efficiently and correctly face similar challenges: sorting out the current legal position on an issue quickly despite the piecemeal way that the SPC develops the law, locating and assessing the validity of historical documents, easily identifying special arrangements, and for cross-border cases, understanding how to correctly implement international conventions, treaties and practices and correspondingly arrangements or related provisions concerning cases involving Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan parties.

One experienced senior judge in a local court noted that judges are often asked to rotate among divisions (tribunals) periodically. Senior judges recommend that new joiners read these handbooks to familiarize themselves quickly with a different (and complicated) area of law.

You must be logged in to post a comment.