Among the many reforms set out in mentioned in the February, 2019 Supreme People’s Court ‘s (SPC’s) fifth judicial reform plan outline is improving the mechanism of the Professional Judges Meeting, about which I have previously written. Earlier this month (January, 2021), the SPC issued guidance on professional/specialized judges meetings (I have also translated it previously as specialized judges meetings) , entitled Guiding Opinion on Improving the Work System of Professional Judges Meetings (Professional Judges Meetings Guiding Opinion or Guiding Opinion), (关于完善人民法院专业法官会议工作机制的指导意见), superseding 2018 guidance on the same topic. The earlier guidance had the title of Guiding Opinions on Improving the Working Mechanism for Presiding Judges’ Meetings of People’s Court (For Trial Implementation). The meetings are intended to give single judges or a collegial panel considering a case additional thoughts from colleagues, when a case is “complicated,” “difficult,”, or the collegial panel cannot agree among themselves.

This blogpost will provide some background to the Guiding Opinion, a summary of the Guiding Opinions, a summary of a non-scientific survey of judges, and some initial thoughts.

Background to the Guiding Opinion

The Guiding Opinion is a type of soft law that enables the SPC to say that it has achieved on of the targets set out in the current judicial reform plan. According to a recent article by the drafters, they researched and consulted widely among courts, but that does not mean that a survey went out to all judges. It is further evidence that the SPC is operating as Justice He Xiaorong stated five years ago–” after the circuit courts are established, the center of the work of SPC headquarters will shift to supervision and guidance…”

Judicial reform and the Guiding Opinion

The Professional Judges Meeting Guiding Opinion is linked to #26 of the current judicial reform plan outline, discussed in part in this June, 2019 blogpost. I have bold-italicked the relevant phrases:

#26 Improve mechanisms for the uniform application of law. Strengthen and regulate work on judicial interpretations, complete mechanisms for researching, initiating, drafting, debating, reviewing, publishing, cleaning up, and canceling judicial interpretations, to improve centralized management and report review mechanisms. Improve the guiding cases system, complete mechanisms for reporting, selecting, publishing, assessing, and applying cases. Establish mechanisms for high people’s courts filing for the record trial guidance documents and reference cases. Complete mechanisms for connecting the work of case discussion by presiding judges and collegial panel deliberations, the compensation commission, and the judicial committee. Improve working mechanisms for mandatory searches and reporting of analogous cases and new types of case. (完善统一法律适用机制。 加强和规范司法解释工作,健全司法解释的调研、立项、起草、论证、审核、发布、清理和废止机制,完善归口管理和报备审查机制。完善指导性案例制度,健全案例报送、筛选、发布、评估和应用机制。建立高级人民法院审判指导文件和参考性案例的备案机制。健全主审法官会议与合议庭评议、赔偿委员会、审判委员会讨论案件的工作衔接机制。完善类案和新类型案件强制检索报告工作机制)

Uniform Application of Law

As for why the uniform application of law is an issue, a quick explanation is the drafting of Chinese legislation often leaves important issues unresolved and leaves broad discretion to those authorities issuing more specific rules. To the casual observer, it appear that the Chinese legislature (NPC) “outsources” to the SPC (and Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP) for some issues) the hard job of drafting more detailed provisions. (see Chinalawtranslate.com for many examples and NPC_observer.com for insights about the legislative drafting process). Although the Communist Party’s plan for building rule of law in China calls for legislatures to be more active in legislating (see NPC Observer’s comments), in my view the SPC (and SPP) will continue to issue judicial interpretations, as the NPC and its standing committee are unlikely to be able to supply the detailed rules needed by the judiciary, procuratorate and legal community. Although the general impression both inside and outside of China is that the SPC often “legislates,” exceeding its authority as a court, as I have mentioned several times in recent blogposts, the SPC issues judicial interpretations after close coordination and harmonization with the NPC Standing Committee’s Legislative Affairs Commission.

Professional Judges Meeting Guiding Opinion

The Guiding Opinion is linked to the judicial responsibility system, about which my forthcoming book chapter will have more discussion. Professor He Xin addresses that system, among other topics in his recently published academic article.

The Guiding Opinion authorizes certain senior members of a court (court president, vice president, head of division, as part of their supervisory authority (under the Organic Law of the People’s Courts) to chair meetings of judges (who exactly will attend depends on the court- to discuss certain types of cases and provide advice to the single judge or three judge panel hearing a case. (In my informal inquiries, I have found that interns are sometimes permitted to attend, but sometimes not). The types of cases mentioned in Article 4 of the guiding opinions and listed below are not complete, but raise both legal and politically sensitive issues:

- ones in which the panel cannot come to a consensus,

- a senior judge believes approaches need to be harmonized;

- involving a mass (group) dispute which could influence social stability;

- difficult or complicated cases that have a major impact on society;

- may involving a conflict with a judgment in a similar case decided by the same court or its superior;

- certain entities or individuals have made a claim that the judges have violated hearing procedure.

Before the discussion, the judge or judges involved in the case are required to prepare a report with relevant materials, possibly including a search for similar cases, which may or may not be the same as the trial report described in my July, 2020 blogpost,

The guiding opinions sets out guidance on how the meeting is to be run and the order in which persons speak.

Depending on the type of case involved, a case may be further referred to the judicial committee or the matter may be resolved by the meeting providing their views to the collegial panel.

Article 15 of the guiding opinions provides that participating in these meetings is part of a judge’s workload. The guiding opinions provide that a judge’s expression of views at these meetings should be an important part of his or her performance appraisal, evaluation, and provision, and the materials can be edited into meeting summaries, typical cases, and other forms of guidance materials, which can be used for additional points in performance evaluation. One of the operational divisions of the SPC and at least one circuit court has published edited collections of their professional judges meetings, with identifying information about the parties removed.

Comments

From my non-scientific survey of judges at different levels of court and in different areas of law, my provisional conclusion is as follows. Judges hearing civil or commercial cases seem to hold these meetings more often, particularly at a higher level of court. Criminal division judges seem to hold such meetings less often (at least based on my small sample), but the meetings are considered to be useful.

Frequency seems to depend on the court and the division, with one judge mentioning weekly meetings, while others mentioned that they were held occasionally. Most judges that I surveyed considered the meetings useful, because they provided collective wisdom and enabled judges to consider the cases better. One judge noted that it may also result in otherwise unknown relevant facts coming to light.

I would also add my perception that it also gives the judges dealing with a “difficult or complicated case” (substantively or politically) in a particular case the reassurance that their colleagues support their approach, even if the judges involved remain responsible under the responsibility system. This is important when judges are faced with deciding cases in a dynamic area of law with few detailed rules to guide them, or where the policy has changed significantly within a brief time. My perception is that this mechanism provides a more collegial environment and better results that the old system of having heads of divisions signing off on judgments. I would welcome comments from those who have been there.

The Guiding Opinions provide yet another illustration of how Chinese courts operate as a cross between a bureaucracy and a court, from the rationale for holding the meeting to the use of meeting participation as an important part of performance evaluation.

Although the slogan (of several years ago) is that judges should be treated more like judges, the Guiding Opinion appears to treat lower court judges analogous to secondary or university students, to be given grades for their class participation.

What are the implications of this mechanism?

Litigants and their offshore counsel (Chinese counsel would know this) need to know that the result in their case in a Chinese court may be influenced by judges who are not in the courtroom when their counsel advocates orally. Written advocacy should still have an impact on professional judge committee discussions. It appears that counsel is not informed that the case has been referred to a professional judges committee for discussion and it is not possible for counsel to know who is part of the committee and apply for judges to be recused in case of a concern that there has been a conflict of interest.

Would it result in more commercial parties deciding that arbitration is a better option, as they have better control over dispute resolution in their particular case? My perception is that the decision concerning appropriate dispute resolution is based on other factors, and the existence of the professional judges meeting as a mechanism to provide views to judges hearing a case has little impact on that decision. I welcome comments on that question.

__________________________________________

Many thanks to those who participated in the survey and also to those who commented on an earlier draft of this blogpost.

The Shanghai maritime court’s bilingual white paper for 2014 and 2015 is downloadable in PDF (under the Annual Report tab), the Court News is relatively timely, The case digests are useful and calendar lists upcoming court hearings (however without information concerning how an interested person could attend them). Unusually for a Chinese court website, the Judges tab has photos of judges other than the senior leadership. The Contact Us tab (unusual for a Chinese court) has only telephone numbers for the court and affiliated tribunals, rather than an email (or Wechat account). Of course the information on the Chinese side of the website is more detailed (under the white paper tab, for example, a detailed analysis of annual judicial statistics can be found), and the laws & regulations tab might usefully set out maritime-related judicial interpretations, but most of the information is well organized and relevant. Similar comments can be made about the Guangzhou maritime court’s website (

The Shanghai maritime court’s bilingual white paper for 2014 and 2015 is downloadable in PDF (under the Annual Report tab), the Court News is relatively timely, The case digests are useful and calendar lists upcoming court hearings (however without information concerning how an interested person could attend them). Unusually for a Chinese court website, the Judges tab has photos of judges other than the senior leadership. The Contact Us tab (unusual for a Chinese court) has only telephone numbers for the court and affiliated tribunals, rather than an email (or Wechat account). Of course the information on the Chinese side of the website is more detailed (under the white paper tab, for example, a detailed analysis of annual judicial statistics can be found), and the laws & regulations tab might usefully set out maritime-related judicial interpretations, but most of the information is well organized and relevant. Similar comments can be made about the Guangzhou maritime court’s website (

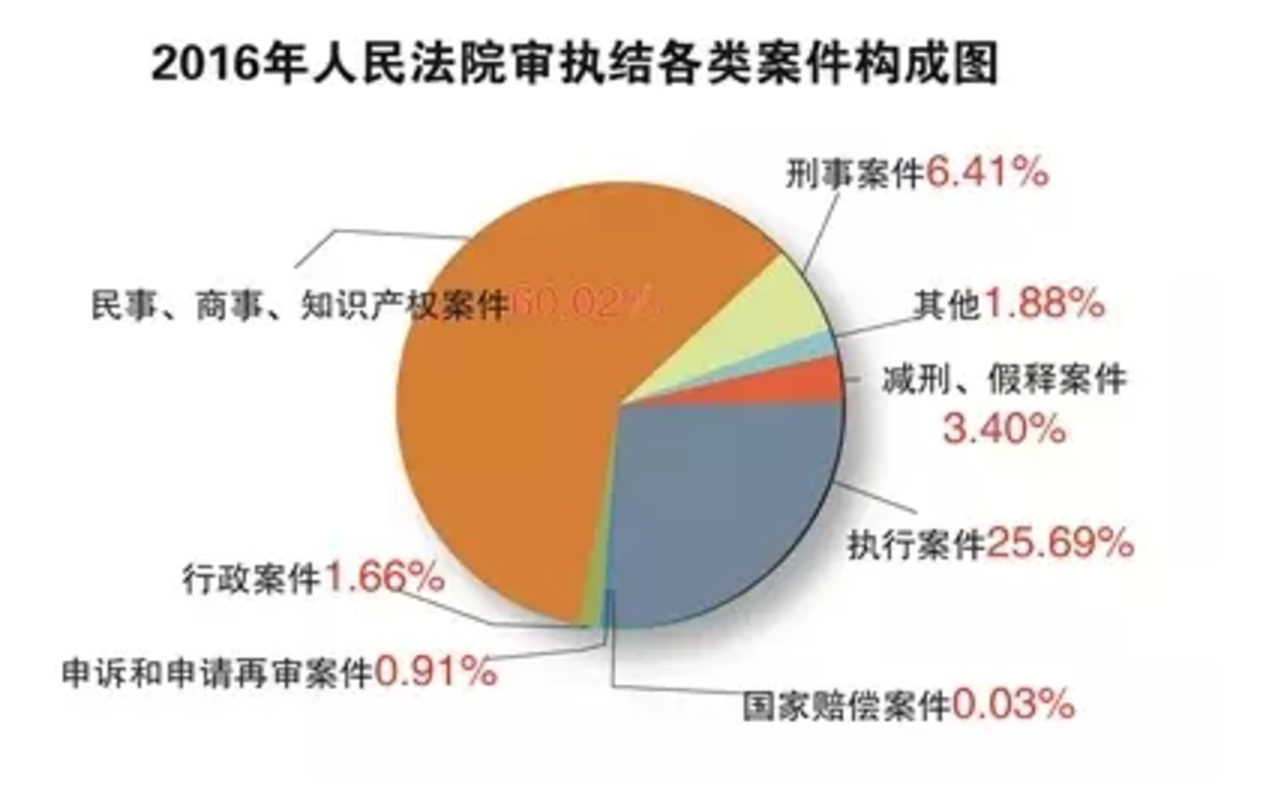

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows:

The pie chart of cases heard, enforced and closed in 2016 shows: Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases.

Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases.

You must be logged in to post a comment.