In November 2023, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued a judicial interpretation intended to encourage and standardize the way that the courts issue judicial suggestions (advice) (司法建议), entitled Provisions of the SPC on Several Issues Concerning Comprehensive Judicial Advice Work (Judicial Advice Work Judicial Interpretation) (最高人民法院关于综合治理类司法建议工作若干问题的规定). For those in jurisdictions in which the SPC’s official website is inaccessible, see this link. When a translation becomes available, I will post it. As a judicial interpretation, its provisions are binding on the lower courts, unlike its predecessor 2012 and 2007 documents. Judicial suggestions (advice), the subject of this recent law review article (with detailed historical background), and promoted in these model cases about which I wrote this summer, are often issued in the context of litigation or after a court reviews a group of disputes. As illustrated by those model cases, it is a function being reinvigorated under President Zhang Jun. It is mentioned briefly in the Civil Procedure and Administrative Litigation Laws but not in the Organic Law of the People’s Courts. Now, as in the era of the Wang Shengjun presidency of the SPC, it is linked to active justice. It is also linked with resolving disputes at source, and the courts participating in social governance. As previously mentioned, resolving disputes at source appears to be derived from Chinese medicine philosophy in seeking to resolve the root cause of disputes by using the data, insights, and multiple functions of the courts to that end. For those interested in comparisons and the possible impact of President Zhang Jun’s Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP) experience on the SPC, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate updated its regulations on procuratorial suggestions in 2018. It is yet another function of the Chinese courts that has its roots in the Soviet system.

This quick blogpost flags what is new, the issues to which the new judicial interpretation responds, and places the interpretation in its larger context.

What is New?

The Judicial Advice Judicial Interpretation recasts its content in the language of Xi Jinping New Era political-legal jargon, in contrast to its predecessor document, which dates from 2012 and reflects the political-legal jargon of the period. However, in my view, that would be insufficient to merit a judicial interpretation. Given that judicial advice of a particular type has become a priority under President Zhang Jun, the judicial interpretation is intended to guide other divisions and entities within the SPC and the lower courts to provide judicial advice that better reflects SPC leadership priorities. It therefore:

- addresses judicial advice work on “comprehensive” matters, that is outstanding problems in the field of social governance that cause frequent conflicts and disputes and affect economic and social development and the protection of the people’s rights and interests. It should propose improvements and improvements to the relevant competent authorities or other relevant units.

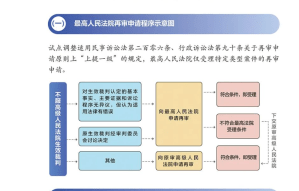

- specifies that when judicial advice is submitted to a government authority, it shall generally be submitted to the competent authority at the same level within the jurisdiction of the court, and not issued to an authority at a bureaucratic level above the court issuing the advice. The judicial interpretation does not permit cross-jurisdictional judicial advice. If the issues require measures to be taken by a relevant authority in another place, the court in question must report the matter to the corresponding superior people’s court for decision. This was stressed by several local judges whom I contacted. I note that according to a report that the Shanghai Financial Court in the summer of 2023, issued 35 items of judicial advice, including to certain central departments (People’s Bank of China and the State Administration of State-Owned Assets, but presumably that court coordinated with the SPC when doing so;

- it requires the court to contact the entity that is proposed to receive the advice, to listen to their views;

- imposes a two-month deadline for the entity receiving the advice to respond (and the advising court to chase up the advised);

- more strongly stresses the “principle of necessity,” i.e., is it necessary to issue this judicial advice, to avoid judicial advice being issued for its own sake (or more properly, to meet internal performance indicators of courts);

- requires judicial advice to be discussed and approved by a court’s judicial committee, rather than the responsible court leader, as in the 2012 document;

- specifies when judicial advice should be copied (抄送) to superior institutions;

- does not specifically cancel the 2012 document, but provides that the provisions in interpretation supersede ones in the earlier document if they are inconsistent.

- requires a court to report on its judicial suggestions as part of its report to the corresponding people’s congress; and

- standardizes format.

There is no requirement of greater transparency but some local courts have posted some information about their judicial advice. The Shanghai Maritime Court is one court that posts judicial advice and responses, some other courts issue more limited information.

Surmising from the article published by the drafters of the interpretation recently in the SPC journal Journal of Applied Jurisprudence (the understanding and application), all of whom are affiliated with the SPC’s Research Office, that office took the lead in drafting this interpretation. It is to be expected that the Research Office took the lead because it often deals with cross-institutional issues.

Ongoing issues

I derive the comments in this section from Ms. Dou Xiaohong’s recent article in the National Judges College academic journal Journal of Law Application (法律适用). She did a deep dive into several thousand items of judicial advice issued in province “S” over the last several years and a more limited number from other provinces and did some cross-jurisdiction comparison. Some of the comparisons work better than others, but it does not take away from the main focus of the article. She works in the Research Office of the Sichuan Provincial Higher People’s Court so “S” likely refers to Sichuan. Presumably, the drafters of the judicial interpretation were aware of her article. She characterizes judicial advice as a form of soft law governance. She found (among other points):

- most judicial advice related to a single case or similar cases, with comprehensive advice accounting for 14%, with most case suggestions relating to typos and omissions in documents (performative judicial advice);

- almost half of the judicial advice “disappears” (is ignored by the recipient of the advice;

- staff of the recipient administrative departments that the author surveyed were unaware that the recipient department was obliged to respond;

- Under the current pressure of cases, it is difficult for judges to have “extra” time and energy to allocate to giving judicial advice.

Ms. Dou makes a number of suggestions, not all of which the drafters of the judicial interpretation incorporated:

- incorporate better reporting to the relevant people’s congress

- incorporate a “comply or explain” principle;

- involve the supervision/Party disciplinary authorities if the matter involves the violation of law or discipline;

- promote greater transparency of judicial advice by the courts and the recipients of the advice, so that there is greater awareness of judicial advice.

Greater significance

The promotion of higher quality judicial advice (suggestions) through the issuance of this judicial interpretation is another example of the development of the Chinese courts in the Xi Jinping New Era, post the 2019 Zhengfa (political-legal) reforms, stressing the role of the courts in social governance. Unlike some of the other aspects of “active justice,” judicial advice has its roots in legislation, although it is not mentioned in the Organic Law of the People’s Courts. This interpretation highlights a function of the Chinese courts that has existed for many years but has more recently become more important to SPC leadership. Transparency concerning judicial advice is uneven throughout the courts, and it is unclear the extent to which the SPC itself provides judicial suggestions. Lower court practice appears to vary. It appears from Ms. Dou’s article that many lower court judges are more focused on closing cases than issuing soft law judicial advice and providing advice for the sake of meeting a performance target. However, it may also depend on the subject of the judicial advice and whether the recipient perceives the advice provided by the courts as useful, as some local judges have mentioned to me that well-targeted judicial advice has led to inter-institutional discussions. The requirement of “listening to the views” of the entity that is to receive the advice (i.e. receiving their assent) is likely to result in fewer items of judicial advice issued, as courts are likely to consider the procedure too troublesome. However, we will need to wait for the revamped performance indicators under discussion to be released to understand better what the longer-term implications of this judicial interpretation are likely to be.

_____________________________

Many thanks to those who commented on an earlier draft of this blogpost.

In late November (2018), the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued its latest transparency policy. The question is, after reading past the references to the 19th Party Congress and the ideology guiding this document, is what, if anything new does it require of the lower courts (and of itself)? And why? Decoding this

In late November (2018), the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued its latest transparency policy. The question is, after reading past the references to the 19th Party Congress and the ideology guiding this document, is what, if anything new does it require of the lower courts (and of itself)? And why? Decoding this  The team of researchers at the Institute of Law, China Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) evaluated court websites in this volume, advising the courts to “consider judicial openness from the viewpoint of public users,” and expand transparency of judicial statistics, devote manpower to updating court websites, and put some order into chaotic judicial transparency. On December 10, a team from the CASS Institute of Law

The team of researchers at the Institute of Law, China Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) evaluated court websites in this volume, advising the courts to “consider judicial openness from the viewpoint of public users,” and expand transparency of judicial statistics, devote manpower to updating court websites, and put some order into chaotic judicial transparency. On December 10, a team from the CASS Institute of Law

You must be logged in to post a comment.