Annually thousands of petitioners visit China’s courts, particularly the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and its two circuit courts, to seek relief from injustices in the lower courts (and sometimes other injustices).

The #2 Circuit Court, located in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, has as one of its goals improving the way the courts in China’s northeast deal with cases in which ordinary people challenge government action, under the Administrative Litigation Law. (Additionally, it hears a range of civil cases, as well.) The court is doing that through issuing a set of documents (to be analyzed in a future blogpost) and a research report. (For those not familiar with what the SPC does, when the SPC looks into an issue, it often designates a research team to visit lower courts and review some of their files.) The chief judge of the #2 Circuit Court, Judge Hu Yunteng, and two colleagues looked into the question of why so many petitioners in Shenyang have grievances about administrative litigation in the lower courts.

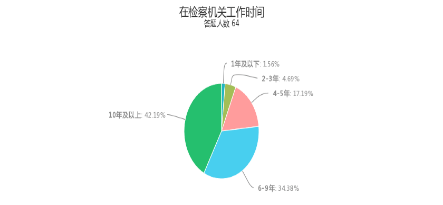

According to the study, one-quarter of the 5000 petitioners whose visit was registered by the court in the first 11 months of 2015 complained about injustice in administrative cases, while those cases constituted only 2% of the overall caseload of the three northeastern provinces. According the study, most of the petitioners who visited the court were not registered. From other statistics, a total of 33.000 visitors petitioned the court. In 2015, the #2 Circuit Court heard almost 200 administrative cases (accepted 193, closed 189, while in 2016, it accepted 691 administrative cases and closed 687). Who are these petitioners in these cases, why are they petitioning, and what should be done about it?

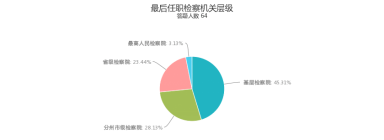

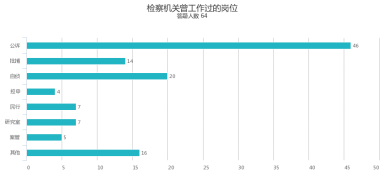

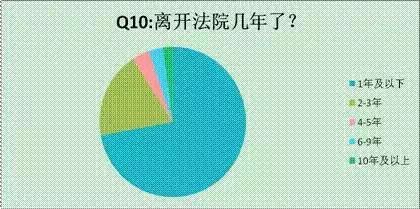

Who are the petitioners?

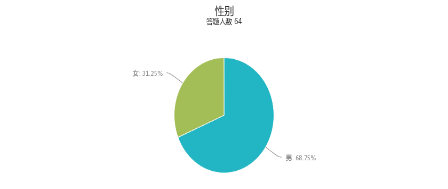

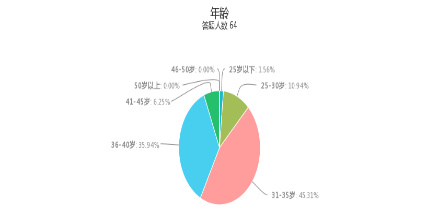

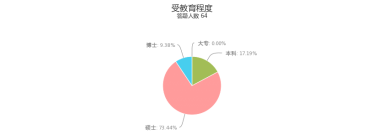

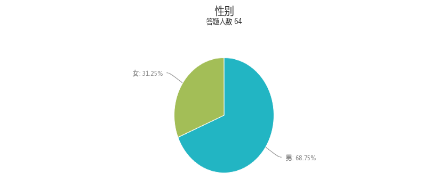

- The petitioners are mostly older, uneducated men from Liaoning Province. The demographics:

- 47% are over 60, with 33% between the ages of 50 and 60;

- 64% are men, 80% from Liaoning, with the remaining 20% from Jilin and Heilongjiang;

- Most are from the countryside or unemployed, with very few represented by lawyers.

They often come repeatedly and in groups. They come in groups because of a group grievance, often relating back years and sometimes several decades. Why Liaoning? The court’s location in Shenyang means that it is more accessible to them, the province is more populous and has historically had more administrative cases. The peak of petitioning was in March, 2015 and is now has stabilized at a lower number.

Their grievances

The grievances are what the SPC (and the Communist Party) entitle “people’s livelihood,”–cases challenging government land requisition and compensation demolition of real property; administrative inaction, and release government information. Of those, 66% are related to land requisition, generally when the government requisitions land in old city and shantytowns. The core reason, according to the judges’ analysis, is local government failure to comply with the law in the process, causing all sorts of administrative litigation and large numbers of petitioners.

Another reason for petitioning is that the rationale in court decisions in these administrative cases is inadequate or totally unclear, with overly simple descriptions of the facts. The decisions often do not make sense; the result is sometimes correct but the reasoning entirely wrong.

If court decisions do not make sense, naturally it will lead to the litigant reasonably suspecting their legality. In some cases the courts failed to review the legality of the administrative action, failing to mention obvious illegalities, simply saying the defendant had not infringed the litigant’s rights. .

Why administrative cases?

Judge Hu and colleagues identified a number of factors causing the ongoing large number of petitioners aggrieved by administrative cases, both external and internal to the courts. The report often refers to “some courts” acting in a certain way, without quantifying the percentage–leading the careful reader to wonder whether it really means “most,” but the judges are reluctant to say so. Their analysis is summarized below.

- Status of the courts

The basic reason is that the constitutional status of the court has not been implemented. “Big government, small court” (大政府,小法院) is an undeniable fact. A court has the status of a department at the same level of government, so under this structure, it cannot be a countervailing force vis a vis the same level of government. When a court is hearing a case, the defendant county head, as deputy Party secretary calls the court president in “for a chat.” If the status of the court in the political system is not changed, it cannot decide cases independently and the rate of petitioning about administrative cases will not go down.

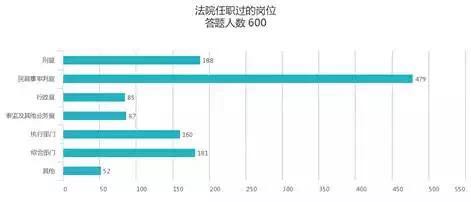

2. Structure of administrative trial divisions

Local courts have jurisdiction over most local administrative cases, but they are under the control of local government, which interferes in every aspect of the case. The local courts make decisions that violate the law, ordinary people’s faith in the justice system declines, so many petitioning cases.

3. Court problems

The ideal of justice for the people not implemented, because some courts, in the name of “serving the greater situation,” stress protecting local stability but fail to protect people’s rights, issuing illegal decisions, harming the prestige of the judiciary, causing disputes between officials and ordinary people that could have been resolved through legal means to be pushed into petitioning.

Cases are bounced back and forth between courts, with no court undertaking a serious review of the case. Courts are seeking to close cases without resolving the underlying issues. With the courts as the place for resolving social disputes and amendment of the Administrative Litigation Law (expanding its jurisdiction), aggrieved litigants, holding sheafs of court decisions are petitioning higher courts, particularly the #2 Circuit Court. If the reasoning is not clear or transparent, ordinary people will just think it is “officials all protecting one another” and petition.

Compounding the problem is weakness in the administrative divisions in the courts and the reception office of the courts. The administrative divisions do not have many cases, so outstanding judges are reassigned, and the team of judges in these divisions is unstable. In the reception office of the lower courts, staff often fails to explain the law to litigants, and are high-handed.

Litigants

Litigants often not educated, do not understand the law, and insist on their view, thinking that if they make a fuss, the issue will be solved.(My former student wrote an account of her experience dealing with petitioners in the #1 Circuit Court, linked here, while the issue of litigation-related petitioners (涉诉信访) receives attention in this long academic article.)

What to do?

The issues with the status of the courts in the political structure a are beyond the authority of the #2 Circuit Court, so what Judge Hu had within his authority to do included:

- doing a better job dealing with petitioners at the court;

- training lower courts to better handle administrative cases;

- better communicating with Party/government, including arranging training for the courts and Party/government, so that officials better understand their obligations under the law;

- doing a better job of public education (宣传教育) through publicizing cases.

Comments

The authors do not venture comments on whether the situation that they describe is typical for other areas of the country, but a quick search reveals courts in other areas of the country raising many of the same issues.

Will the current judicial reforms be able to deal with some of the issues raised by the authors of this study? Only partially, it seems. The future change in appointment and funding, better training for and treatment of local judges should be helpful. The 2015 regulations forbidding leading official interference in court cases should, in theory, reduce local government official interference in the local courts, but more needs to happen to educate local officials to comply with the law. Regulations issued earlier this year mandating legal counsel for Party and state organs may be helpful in the long term. It may be helpful for the #2 Circuit Court to reach out to local lawyers to advise petitioners, as the #1 Circuit Court has done, but whether local lawyers are willing to do so (on a pro-bono basis, as is true in Shenzhen), or possibly that they are concerned that they may be accused of trouble-making under new Ministry of Justice regulations remains to be seen. It is clear from the report that deep-seated attitudes towards law and ordinary people held by government officials are changing only very slowly.

During the Mid-Autumn festival, several of the major legal Wechat accounts carried articles deploring the latest report of violence against judges in a Shandong bank (which occurred on 8 September) (and making caustic comments about the local authorities), attracting hundreds of thousands of page views. An

During the Mid-Autumn festival, several of the major legal Wechat accounts carried articles deploring the latest report of violence against judges in a Shandong bank (which occurred on 8 September) (and making caustic comments about the local authorities), attracting hundreds of thousands of page views. An  Chinese courts are paying more attention to the use of precedent in considering how to decide cases. (Two of my fellow bloggers,

Chinese courts are paying more attention to the use of precedent in considering how to decide cases. (Two of my fellow bloggers,

nths. [The original Caixin report has been taken down, but has been republished by Hong Kong’s

nths. [The original Caixin report has been taken down, but has been republished by Hong Kong’s

On 1 August, President Zhou Qiang of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) inaugurated the SPC’s new enterprise bankruptcy and reorganization electronic information platform, linked

On 1 August, President Zhou Qiang of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) inaugurated the SPC’s new enterprise bankruptcy and reorganization electronic information platform, linked  no further information is available. This section is intended to provide the most recent annual report, related litigation, and information on assets of the company from the industrial and commercial authorities’ database and enable “one-stop shopping” for distressed assets.

no further information is available. This section is intended to provide the most recent annual report, related litigation, and information on assets of the company from the industrial and commercial authorities’ database and enable “one-stop shopping” for distressed assets. What few recognize is that the millions of non-guiding cases on the Supreme People’s Court’s

What few recognize is that the millions of non-guiding cases on the Supreme People’s Court’s

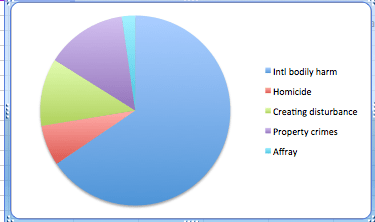

While most of the world is mesmerized by the high PISA scores of students in Shanghai schools, and the impressive achievements of Chinese students on standardized tests, a problem that has escaped the attention of most Chinese authorities (and the outside world) is violence in Chinese schools. In time for Children’s Day (June 1), a team of researchers at the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) published a

While most of the world is mesmerized by the high PISA scores of students in Shanghai schools, and the impressive achievements of Chinese students on standardized tests, a problem that has escaped the attention of most Chinese authorities (and the outside world) is violence in Chinese schools. In time for Children’s Day (June 1), a team of researchers at the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) published a

As highlighted in a December,2015 post on

As highlighted in a December,2015 post on

You must be logged in to post a comment.