Late last year, some followers asked me to describe some of the principal sources for Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) research. I’ll do this in several posts, as few (particularly outside of China) seem to be aware of the range of publicly available publications of the SPC and its many affiliated entities.

The first set of publications I’ll introduce are the journals edited and written (at least in part) by the trial divisions and other offices of the SPC. As far as I know, they are only in printed form. That means that those outside of China are not aware of their existence. The readers of these journals are specialists in the particular field. Many, but not all of them are published by the People’s Court Press (人民法院出版社), which has a retail bookshop near the SPC (see the photo above). I have a special fondness for that bookshop because I purchased judicial handbooks in its predecessor over thirty years ago, triggering my interest in the SPC. Editing these publications is one of the (unrecognized) responsibilities of SPC judges and for that reason, the publication schedule seems to vary widely,

Considering the functions of the SPC, these journals should be best classified as a form of lower court guidance. For local judges, participating in editing or having an article included in one of these journals is considered an accomplishment for performance indicator purposes.

The publications flag new issues facing the judiciary in the specialized area involved, typical cases, and sometimes analysis of foreign laws or regulations. Each journal has a slightly different format.

-

金融法治前沿(Frontier(s) of Financial Law)

This publication should be of interest to those who read Professor Mark Jia’s Special Courts, Global China, and are interested in researching the latest developments concerning China’s financial courts and related financial regulatory issues. The domestic readers of this journal are likely to be judges in the three financial courts or in the financial division of other courts, legal personnel in the financial regulators, interested academics, lawyers focusing on financial law and regulations, as well as in-house counsel in banks and other financial institutions.

Unlike most other journals in this group, this one is a collaboration between the courts and the regulators. The principal members of this collaboration are the SPC’s #2 Civil Division (which focuses on domestic commercial law issues), the legal department of the People’s Bank of China (人民银行条法司), the National Financial Regulatory Administration, related departments of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), and the Shanghai, Beijing, and Chengdu-Chongqing Financial Courts. One of the related courts takes responsibility for editing each issue. When I was last in Beijing, I purchased issue #2, dated April, 2024. The court that took responsibility for editing was the Shanghai Financial Court, The content includes:

- “frontier issues,” with contributions from all the regulators, on such topics as the application of Chinese financial regulations abroad: coordination between the Insurance Law and Civil Code; and internet finance disputes;

- Typical cases;

- Discussion of Specialized Questions

- Foreign and Hong Kong [and Macau ] finance law issues. Issue #2 includes an article comparing EU and Chinese insurance company recovery and resolution issues, the author of which is an official of a provincial-level bureau of the National Financial Regulatory Administration. The author notes that “the operations of some small and medium-sized insurance are possibly facing difficulties” and the EU and British frameworks provide useful regulatory models for China to consider in designing a recovery and resolution system for insurance companies.

Guidance on the Trial of Duty-Related Crime (职务犯罪审判指导)

This publication should be of interest to those who are interested in legal issues (and the broad range of factual situations) related to bribery and corruption in China. Judging from announcements on WeChat, the readers of this journal appear to include procurators (prosecutors), criminal division judges, criminal defense lawyers, and public security officials.

Although none of the introductory essays have mentioned this, I surmise that this journal was founded because the distinctive issues relating to duty crimes “outgrew” the journal of the five SPC criminal divisions, Reference to Criminal Trial (刑事审判参考). So far, only two issues have been published, #1, published in 2022, and #2, published in the last month or two. The SPC’s #2 Criminal Division edits the journal. The content of issue #1 includes:

- Analysis of the application of law (法律适用分析), providing analysis of typical issues in the determination of facts, acceptance of evidence, application of law and the determination of sentencing, providing insights into the thinking and reasoning of judges. This WeChat article provides a quick summary of many of the cases in this section in issues #1 and #2, but without the colorful detail, such as the case involving the lovers Mr. and Ms. Wang, one a deputy department head in a Central state-owned enterprise, the other the assistant to the head of a state-controlled bank in city T (presumably Tianjin).

- [Professional ] judges meeting summaries. Many SPC divisions (civil or administrative) have published collections of meeting summaries, but this is the first time I have noticed them being made public on criminal law issues. The first summary involves a 2021 case in which the local Party discipline/supervision authorities investigated the personnel in the courts, prison, and procuracy for issues relating to the crime of bending the law for selfish ends or twisting the law for a favor. That involved a case in which a criminal was sentenced in 1992 to 15 years for intentional homicide, but was released in 1996, after several sentence reductions and but who committed the crime of false accusation in 2019 (no details). The disputed issue was whether the statute of limitations had lapsed.

- Difficult issues in practice–two articles, including one by Judge Wang Xiaodong, the now-retired head of the #2 criminal division on issues related to anti-corruption legislation in the New Era (pointing out problems with the substantive and procedural law);

- Exchange of experience–this provides a proposed outline (and explanation) for the courts to hear duty crimes in the first instance (人民法院审理职务犯罪案件刑事第一审普通程序庭审提纲(建议稿)(the link has the text of the outline). The explanation mentions it was issued to provide more consistency in the trial of these cases;

- Legal regulation (the Supervision Law and Supervision Law Implementing Regulations);

- Criminal policy–summary of a policy document (not full text) and press release issued by the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI)/Supervision Commission, Central Organization Department, Central United Front Department, the Central Political-Legal Commission, the SPC and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Opinions on Further Promoting the Investigation of the Giving and Acceptance of Bribes” (the linked article provides the same content). The summary mentions the possible establishment of a joint punishment mechanism and the implementation of a “blacklist” system for bribers.

- Theoretical disputes

- Practical Research

- Selected Typical Judgments (the last three sections had no content in issue #1.)

______________________________________

Many thanks to a knowledgeable person for his perceptive comments on an earlier draft of this blogpost.

I have spent some time decoding Supreme People’s Court (SPC) President Zhou Qiang’s

I have spent some time decoding Supreme People’s Court (SPC) President Zhou Qiang’s

Wechat, as most people with an interest in China know, has become the preferred form of social media in China. The legal community in China has taken to it too.

Wechat, as most people with an interest in China know, has become the preferred form of social media in China. The legal community in China has taken to it too.

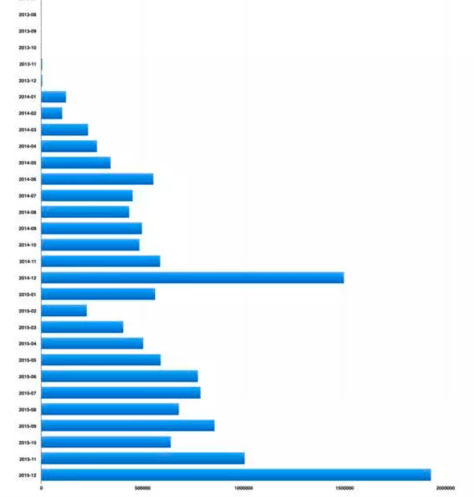

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued 2016 data on bankruptcy cases on 24 February: 5665 cases were accepted by the Chinese courts while 3602 were closed. This is up substantially from

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued 2016 data on bankruptcy cases on 24 February: 5665 cases were accepted by the Chinese courts while 3602 were closed. This is up substantially from

Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases.

Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases. The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) database, China Judgments Online, receives good marks from most commentators inside and outside of China and it is one of the successes of the judicial reforms that President Zhou Qiang often discusses with visiting foreign guests as well as domestic officials. Only now has a team of researchers from Tsinghua University drilled down on the case database (but only through 2014, because the data was not complete for 2015) (short version found

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) database, China Judgments Online, receives good marks from most commentators inside and outside of China and it is one of the successes of the judicial reforms that President Zhou Qiang often discusses with visiting foreign guests as well as domestic officials. Only now has a team of researchers from Tsinghua University drilled down on the case database (but only through 2014, because the data was not complete for 2015) (short version found

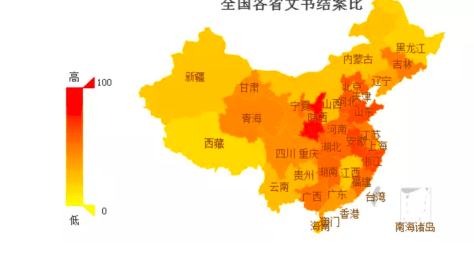

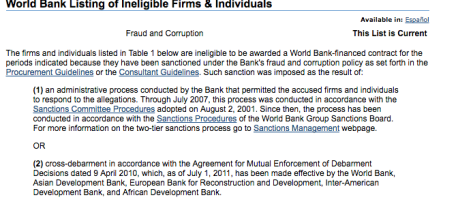

The Supreme People’s Court and other Chinese government institutions have been making increasing use of name & shame lists to call attention to illegal behavior by institutions and individuals and to prevent them from benefiting from their illegal behavior (as I discussed in

The Supreme People’s Court and other Chinese government institutions have been making increasing use of name & shame lists to call attention to illegal behavior by institutions and individuals and to prevent them from benefiting from their illegal behavior (as I discussed in

During the Mid-Autumn festival, several of the major legal Wechat accounts carried articles deploring the latest report of violence against judges in a Shandong bank (which occurred on 8 September) (and making caustic comments about the local authorities), attracting hundreds of thousands of page views. An

During the Mid-Autumn festival, several of the major legal Wechat accounts carried articles deploring the latest report of violence against judges in a Shandong bank (which occurred on 8 September) (and making caustic comments about the local authorities), attracting hundreds of thousands of page views. An  Chinese courts are paying more attention to the use of precedent in considering how to decide cases. (Two of my fellow bloggers,

Chinese courts are paying more attention to the use of precedent in considering how to decide cases. (Two of my fellow bloggers,

nths. [The original Caixin report has been taken down, but has been republished by Hong Kong’s

nths. [The original Caixin report has been taken down, but has been republished by Hong Kong’s

You must be logged in to post a comment.