Several days ago, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued the brief judicial interpretation, translated below:

Several days ago, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued the brief judicial interpretation, translated below:

Supreme People’s Court

Reply Concerning issues related to the Application of Article 225 (para 2) of the Criminal Procedure Law

Approved by the 1686th meeting of the Judicial Committee of the Supreme People’s Court, in effect from 24 June 2016

Fa Yi(2016) #13

To the Henan Higher People’s Court:

We have received your request for instructions concerning the application of Article 225(2) of the Criminal Procedure. After consideration, we respond as follows:

I. For cases remanded to the second instance people’s court for retrial by the Supreme People’s Court, on the basis of “People’s Republic of China Criminal Procedure Law” Article 239 (2) [if the Supreme People’ s Court disapproves the capital punishment sentence, it may remand the case for retrial or revise the sentence] and Article 353 of the Interpretation of the “Supreme People’s Court on the application of the People’s Republic of China Criminal Procedure Law [where the Supreme People’s Court issues a ruling on non-approval of the death penalty sentenced under a case, it may remand the case to the people’s court of second instance or the people’s court of first instance for retrial, depending on the actual circumstances of the case…], having ruled not to approve the death penalty,and regardless of whether the people’s court of second instance had previously sent the case back to the first instance court on the grounds that original judgment’s facts were unclear or evidence was insufficient; in principle, it must not be sent back to the original first instance court for retrial; if there are special circumstances requiring the case to be sent back to the first instance court for a retrial, it must be submitted to the Supreme Court for approval.

II. in cases where the Supreme People’s Court had ruled to disapprove the death penalty and remanded the case to the second instance people’s court for retrial, and the second instance people’s court had remanded the case to the first instance court according to special circumstance, after the first instance court has issued its judgment and the defendant has appealed or the people’s procuratorate has made a protest, the second instance people’s court should issue a judgment or ruling according to law, and must not send the case back for re-trial, according to the specifics of the case, which had sent the case to the first instance court for retrial.

So replied.

_________________________________________________________

What is this and what does this mean?

This is a judicial interpretation by the SPC in the form of a reply, as explained here. It is a reply (批复) to a “request for instructions” from a lower court relating to an issue of general application in a specific case. The Henan Higher People’s Court had submitted a request for instructions, likely with two or more views on the issue, but the lower court’s request is not publicly available. It is likely that practice among provincial courts had been inconsistent, and therefore the SPC is harmonizing judicial practice through this reply. As required by the SPC’s regulations on judicial interpretations, it must be approved by the SPC’s judicial committee as a judicial interpretation.

This gives further details to the SPC’s capital review procedures, requiring second instance (generally provincial level courts) to hear retrials of cases remanded by the SPC and not instructing those courts not send cases back to the first instance court for retrial. It also requires the second instance court to rule on a defendant’s appeal or procuratorate’s protest and not remand the case back to the first instance court, expediting the final consideration of these cases and limiting the number of remands of these cases.

Is this a positive development for the protection of the rights of the defendants (the defendants in the typical drugs cases announced by the SPC recently were mostly peasants), by requiring the second instance court to hear these cases, away from the public pressure where the crime occurred? In a 2013 article, criminal defense lawyer Sun Zhongwei described the pressure on a local first and second instance court is under from the victim’s family and the local Party committee and government, and how the institutions use delay and remanding the case to the procuratorate and public security for additional investigation to avoid making difficult decisions that will alienate local authorities.What has the role of defense counsel been in these cases? Have most defendants been advised by counsel? Was the delay in final resolution in these cases an issue discussed by the Central Political Legal Committee?

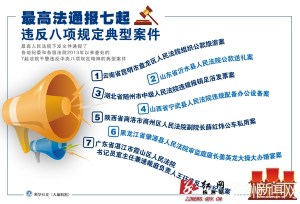

What was the rationale for issuing this interpretation at this time? Is it a measure to promote the efficiency of the courts, by expediting finality in criminal punishment, so that the courts can announce in a timely manner their crime fighting accomplishments and typical cases?A headline on one of the SPC’s websites reporting on 30% increase in drugs crime convictions in the provincial level courts may indicate which is valued more–“People’s courts across the country cracked down hard on drug crime.”

Or is it linked to planned reforms to the criminal justice system and improvements to the legal aid system for criminal defendants approved by Xi Jinping and other top leaders on 27 June?

You must be logged in to post a comment.