The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and Procuratorate (SPP) issued their first judicial interpretation of 2017, Provisions on Several Questions Concerning the Application of the Procedure of Confiscating Illegal Gains in Cases Where the Criminal Suspects or Defendants Absconded or Died (Asset Recovery Interpretation). It went into effect on 5 January. It is possible that the timing is related to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection annual conference.

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and Procuratorate (SPP) issued their first judicial interpretation of 2017, Provisions on Several Questions Concerning the Application of the Procedure of Confiscating Illegal Gains in Cases Where the Criminal Suspects or Defendants Absconded or Died (Asset Recovery Interpretation). It went into effect on 5 January. It is possible that the timing is related to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection annual conference.

It is an important piece of quasi-legislation enabling the Chinese authorities to recover assets that are the proceeds of corruption and other crimes within China and internationally, where the criminal suspect or defendant has absconded, left the jurisdiction, or died. If your jurisdiction is one that already has in place treaty arrangements with China that will enable the Chinese authorities to seek recovery of assets, the interpretation bears close review. Canada, for example, has supplemented its criminal judicial assistance treaty with a specialized asset recovery agreement.

Background

The recovery and forfeiture of the proceeds of corruption and other crimes has become a priority issue because the anti-corruption campaign under Xi Jinping has made it so. Although the Criminal Procedure Law was amended in 2012 to enable the authorities to confiscate assets of persons who had or were suspected of committing certain major crimes (see Articles 280-283), in the view of the SPP and SPC, the Asset Recovery Interpretation was needed because the law itself was inadequate. The drafters identified four issues:

- the range of crimes to which asset recovery could be applied was too narrow;

- major disagreements existed concerning procedures and standards of evidence;

- local authorities lacked experience with asset recovery;

- procedures and relative responsibilities of different authorities were unclear, making it difficult when negotiating with foreign governments.

The actual drafting of the Asset Recovery Interpretation began shortly after the 4th Plenum and before the Skynet operation was launched.The drafting of this interpretation was a high-profile project for the two institutions. The SPP and SPC worked with the CCDI, the Central Political-Legal Committee, National People’s Congress Legislative Affairs Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Justice, and other authorities to produce a draft a practicable system that could be used when negotiating with foreign countries, meet the policy targets of the Party, and contain legal standards specific enough for the procuratorate and courts.

The Asset Recovery Interpretation also draws on the interactions the SPP and SPC have had as part of multi-institutional dialogues on the recovery of the proceeds of corruption with a variety of multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, as well as bilateral interactions such as with the United States government, for example, through the US-China Joint Liaison Group on Law Enforcement Cooperation.

The drafting of the Asset Recovery Interpretation was flagged in the Fourth Plenum Decision:

Strengthen international cooperation on anti-corruption, expand strength to pursue stolen goods and fugitives overseas, as well as for repatriation and extradition.

Asset recovery through the courts was included in the SPC’s 4th Five Year Plan:

16. Standardize judicial procedures for disposing of assets involved in a case.Clarify the standards, scope, and procedures for people’s courts’ disposition of property involved in the case. Further standardize judicial procedures in criminal, civil and administrative cases for sealing, seizing, freezing and handling of assets involved in a case.

…expand the scope covered by regional and international judicial assistance. Promote the drafting of a Judicial Assistance Law in Criminal Matters.

The drafting of the interpretation was the responsibility of the #2 Criminal Division of the SPC and the Law and Policy Research Office of the SPP.

Some important provisions

This blogpost cannot provide a comprehensive description of the interpretation which expands/further details the procedures set out in Articles 280-283 of the Criminal Procedure Law and related law, but notes the following provisions.

1. The Asset Recovery Interpretation expands the scope of the crimes to which asset recovery applies. Article 280 of the Criminal Procedure Law authorizes a people’s procuratorate to apply to a court for confiscation of illegal gains and other property related to the case in serious crimes (重大犯罪案件) such as corruption, bribery or terrorist activities where the criminal suspects or defendants have absconded and have not been found one year after the public arrest warrants were issued, or where the criminal suspects or defendants have died.

Article 1 of the interpretation expands the term “such as” (等) by specifying that confiscation can be applied to the following crimes among others:

- Corruption; embezzlement of public funds; possessing huge amounts of property from unknown sources; concealing overseas savings; privately dividing state-owned assets; privately dividing assets that had been confiscated;

- Bribe-taking; exploiting influence to take bribes; bribery by an individual or entity; giving bribes to persons with influence; introducing bribery;

- Organizing, leading, or participating in terrorist organizations; helping terrorist organizations, preparing to carry out terrorist activities; advocating terrorism or extremism, and incitement of carrying out of terrorist activities; using extremism to sabotage the enforcement of laws; forcing others to wear clothing and signs that advocate terrorism or extremism; illegally possessing articles that advocate terrorism or extremism;

- Endangering state security; smuggling; money laundering, financial fraud; mafia-type organizations, and drugs.

- Telecommunications and internet fraud.

As many others have written in other contexts, some of the crimes listed above have been over-broadly applied in China–some to persons who disagree with the government and others to private entrepreneurs.

Language in extradition treaties is flexible enough to enable foreign governments to refuse to extradite or assist in the recovery of assets from persons that the host government considers a political dissident rather than a criminal. However, those persons can anticipate that their domestic assets may be the subject of confiscation procedures.

2. The definition of assets of crime draws on relevant language in the UN Corruption Convention on proceeds of crime, and so include proceeds of crime that have been transformed or converted, in part or in full, into other property, as well of proceeds of crime have been intermingled with property acquired from legitimate sources.

3.The Asset Recovery Interpretation sets out needed details in the procedure by which assets can be confiscated, including detailing the evidence the procuratorate has to provide to a court in the application for confiscation, matters to be set out in the notice issued by a court that accepts the application; persons to whom the notice should be serviced and media outlets where the notice should be published. (Under Article 281 of the Criminal Procedure Law, the notice concerning the application needs to be in effect for six months.)

Under Article 281, close relatives and interested parties (and their representatives) can apply to attend the court hearing at which the confiscation of assets application is reviewed, but “interested parties” had not been defined, nor had the details of how the first instance and appeal procedures were to be conducted.

4. The Asset Recovery Interpretation details the procedures for seeking international cooperation in the recovery of assets, including the type of order the lower court should issue and documentation that the lower court must prepare. The bundle of documentation must be reported up to the SPC and after the SPC reviews it, the SPC prepares a request letter, the contents of which are specified in the interpretation. These request letters generally are transferred abroad via the Ministry of Justice, which is usually designated the competent national authority under treaty or convention arrangements.

Next steps

The SPC anticipates that the Asset Recovery Interpretation will lead to an increase in cases, but are aware these issues and procedures are new to the lower courts, so it is requiring lower courts to designate certain judges to hear these cases and for these judges to undergo training on the Asset Recovery Interpretation and related issues.

The SPC calls on cooperation with related departments on the recovery of proceeds of crime from abroad, saying that it cannot fight the battle alone. (不能依靠某一个部门单兵作战).

Foreign jurisdictions can anticipate an increase in requests from China and it is likely that the mainland will request that the Hong Kong authorities negotiate a related arrangement. It will raise further concerns for those former Chinese officials accused of the crimes described above living in jurisdictions with an extradition or mutual legal assistance in criminal matters treaty. For lawyers in China and abroad, it represents a new practice opportunity.

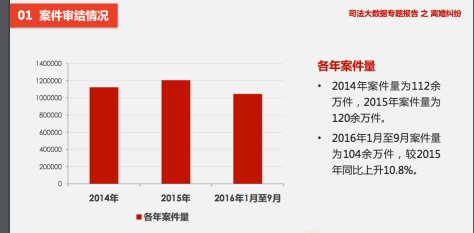

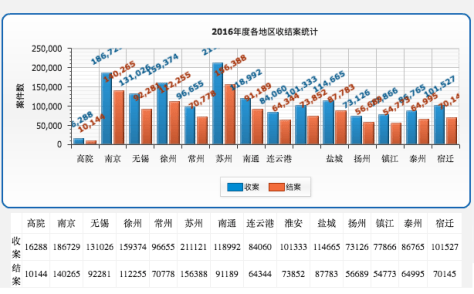

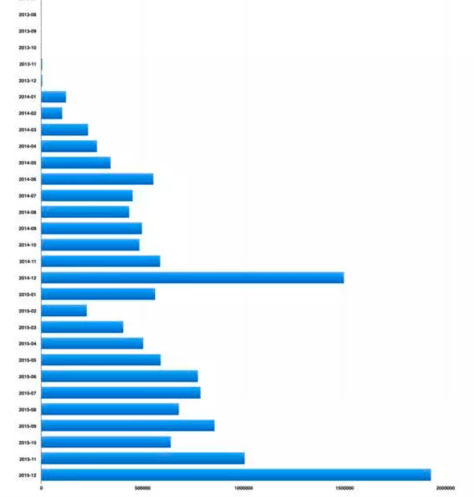

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued 2016 data on bankruptcy cases on 24 February: 5665 cases were accepted by the Chinese courts while 3602 were closed. This is up substantially from 2015, when 3568 cases were accepted. This is an increase of 53.8% over 2015. Of these, 1041 were bankruptcy reorganization cases, up 85.2% over 2015. As this blog has previously reported, long delays in filing bankruptcy cases have meant that practically all bankruptcy cases have been liquidation rather than reorganization cases. This is contrast to the downward trend in bankruptcy cases 2005-2014, shown in the graph published on this earlier blogpost. These numbers represent only a tiny proportion of what the Chinese government terms “zombie enterprises,” but it does show that the SPC has been doing its part to serve the nation’s major economic strategies.

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued 2016 data on bankruptcy cases on 24 February: 5665 cases were accepted by the Chinese courts while 3602 were closed. This is up substantially from 2015, when 3568 cases were accepted. This is an increase of 53.8% over 2015. Of these, 1041 were bankruptcy reorganization cases, up 85.2% over 2015. As this blog has previously reported, long delays in filing bankruptcy cases have meant that practically all bankruptcy cases have been liquidation rather than reorganization cases. This is contrast to the downward trend in bankruptcy cases 2005-2014, shown in the graph published on this earlier blogpost. These numbers represent only a tiny proportion of what the Chinese government terms “zombie enterprises,” but it does show that the SPC has been doing its part to serve the nation’s major economic strategies.

Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases.

Unlike ordinary labor cases, most cases were decided by court judgment, not mediated. In 66% of the cases, the plaintiff’s claim was upheld in whole or part, with a dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims in 28% of cases.

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and Procuratorate (SPP) issued their first judicial interpretation of 2017,

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and Procuratorate (SPP) issued their first judicial interpretation of 2017,  In 2016, the Supreme People’s Court Monitor published 67 posts and had close to 30,000 page views, from 150 countries (regions), primarily from:

In 2016, the Supreme People’s Court Monitor published 67 posts and had close to 30,000 page views, from 150 countries (regions), primarily from:

Thank you very much to all of my followers for following me. I plan to tweak the type of content that I am providing, providing fewer long analytical blogposts, because I want to concentrate on writing a book on Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in the era of reform, in the style of this blog and in my free time work on income-generating projects.

Thank you very much to all of my followers for following me. I plan to tweak the type of content that I am providing, providing fewer long analytical blogposts, because I want to concentrate on writing a book on Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in the era of reform, in the style of this blog and in my free time work on income-generating projects.

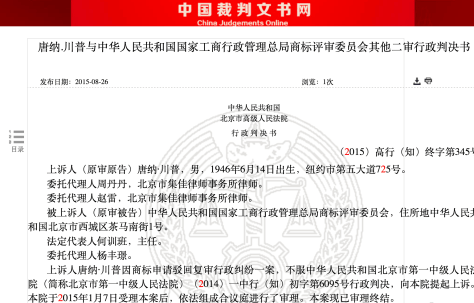

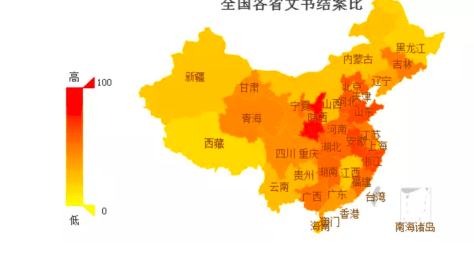

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) database, China Judgments Online, receives good marks from most commentators inside and outside of China and it is one of the successes of the judicial reforms that President Zhou Qiang often discusses with visiting foreign guests as well as domestic officials. Only now has a team of researchers from Tsinghua University drilled down on the case database (but only through 2014, because the data was not complete for 2015) (short version found

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) database, China Judgments Online, receives good marks from most commentators inside and outside of China and it is one of the successes of the judicial reforms that President Zhou Qiang often discusses with visiting foreign guests as well as domestic officials. Only now has a team of researchers from Tsinghua University drilled down on the case database (but only through 2014, because the data was not complete for 2015) (short version found

The Supreme People’s Court and other Chinese government institutions have been making increasing use of name & shame lists to call attention to illegal behavior by institutions and individuals and to prevent them from benefiting from their illegal behavior (as I discussed in

The Supreme People’s Court and other Chinese government institutions have been making increasing use of name & shame lists to call attention to illegal behavior by institutions and individuals and to prevent them from benefiting from their illegal behavior (as I discussed in

You must be logged in to post a comment.