This post is the written and English-language version of a speech I first delivered in Chinese at the annual meeting of the Shanghai Judicial Think Tank Society (Think Tank Society, 上海司法智库学会, sponsored by the Shanghai Higher People’s Court) on November 30, 2024, held at Shanghai Jiaotong University. (The official report on the meeting is available here.) The views are my own and should not be attributed to the Shanghai Higher People’s Court or the Think Tank Society. I would like to express my appreciation to Dean Jiang Huiling(蒋惠岭)and Professor Luo Tianxuan (罗恬漩) of Tongji University for the kind invitation to participate in the meeting. Further acknowledgments can be found at the end of this post.

Front-line judges often tell the author that “judicial reform is a failure,” although the author does not take their words literally. It is their way of expressing dissatisfaction with aspects of the design and implementation of judicial reform. The official view is that judicial reform is a success, and the basic structure (四梁八柱) of judicial reforms has been constructed in the past 10 years, although work continues to be needed in specific areas. The author is not prepared to say simply that judicial reform is a success or failure, particularly when significant gaps in information prevent the author from making a comprehensive, objective, and informed assessment. Although the author has only been a minor player in the complicated drama of drafting, implementing, and internally evaluating judicial reform in the last ten years, she considers herself fortunate to have the opportunity to monitor it closely and know personally many involved.

Within the limits of this short essay, the author focuses on the “front-end” and “back-end” of the judicial reform process. Her focus is on the process of deriving reforms that fit courts with widely different resources, and internal and external environments. The author roots her comments in the highly complex reality of the Chinese courts and with an international perspective.

Front-end Issues

The author considers that the “front-end” of judicial reform is most important–the drafting of judicial reform plans. She considers four aspects particularly important for the overall success of judicial reforms: evaluating local innovations; pilot projects and foreign mechanisms or experience; improving centrally designed mechanisms; and enabling greater stakeholder input into the judicial reform process. Each has separate and common challenges.

The author turns first to local innovations, pilot projects and foreign mechanisms or experience. Pilot projects are undertaken to “test drive” a possible reform while local innovations, draw on local wisdom and institutions to experiment with a new mechanism. She discusses these together because when reformers consider whether these specific experiences are suitable to be promoted nationally, the challenges are similar.

Family trial reforms (家事审判改革) provide a good example because they involve the above three aspects–evaluating foreign experience, domestic innovations, and pilot projects. In the case of family trial reforms, the relevant reform leaders were able to travel overseas to observe family courts and the ecosystem surrounding them and brought foreign experts to China to discuss specific issues and the related institutions needed to make family trial reforms successful.

Given the geopolitical changes of recent years, this type of onsite research is not as easy to accomplish. Foreign experience is particularly challenging to consider in the context of judicial reform. The first issue is understanding the foreign experience accurately, because written materials may not be comprehensive and fail to explain the institutional infrastructure on which the success of the mechanism is based. International travel to experience that mechanism may not be as feasible as previously, given constricted budgets. A third issue is the issue of “moving the foreign plant to Chinese soil,” to consider whether the mechanism will work as anticipated, given that related institutions operate in a different environment from those abroad.

Next to a pair of related mechanisms–pilot projects, which are undertaken to “test drive” a possible reform, and local innovations, which often draw on local wisdom and institutions to experiment with a new mechanism. The author discusses them together because they share a common challenge when reformers consider whether these two specific experiences are suitable to be promoted nationally. A pilot project approved by the Supreme People’s Court is likely to enjoy more resources, guidance from the Supreme People’s Court and possibly the Legislative Affairs Commission of the National People’s Congress (if delegation legislation is involved), support from local court leaders, as well as relevant institutions outside the courts.

The piloting of family trial reforms in recent years provides a good example. A research team based at Xiamen University* assessing those reforms found large disparities in whether those reforms were successful or even implemented, depending on many factors, such as whether the court was in an urban or rural area, the commitment of supporting organizations, whether local court leaders were committed to the reform and the case burden of individual judges. Pilot courts in urban areas could liaise with psychological counselors and mediators trained to resolve family disputes to achieve better outcomes. Rural judges generally did not have such resources available. The research team found that when judges were overburdened with cases, they would revert to usual practice, following reform practice only when needed for court news releases.

Should judicial reformers have anticipated the gap between rural and urban courts, and the cultural differences in different geographies, particularly in rural areas? Now that these gaps are known, what should be done to improve outcomes for rural as well as urban families? Perhaps special arrangements can be considered to support court teams hearing family matters in rural courts, as is done in some other jurisdictions, such as Australia, but that requires further research and analysis. [Family trial reforms are listed in point 6 of the Sixth Five-Year Reform Outline, issued in December 2024].

Next, on the phenomenon of centrally designed measures implemented with apparently limited input from affected persons. One recent example of this is the recently revised trial quality management indicator system (审判质量管理指标体系). Although the official view is that the relevant departments had engaged sufficient research and input from experts (充分调研论证) and one-half year of piloting the new trial quality management indicator system, from the fact that after nine months of official implementation of the system, “in order to reduce the burden on the lower courts (续深化给基层减负工作)” the number of indicators was reduced from 26 to 18 strongly suggests that after the system was fully implemented, the negative reaction from lower court judges was very strong. Had the relevant departments done a more representative survey of the views of lower court judges on this, the embarrassment of reversing themselves within several months could have been avoided.

Reforms designed without involving the personnel directly affected, without stakeholder input, are not likely to meet their goals. It is unlikely that a small team of persons working in Beijing have sufficient evidence, data, and analysis to reflect the varied types of judicial work and the complex environment in which judges work. It is unclear which type of courts piloted the new indicators and whether the piloted courts considered it prudent to provide responses that the relevant departments sought. This author surmises that it could make sense to have different sets of indicators for urban and rural courts, instead of having a single standard for all, but making that recommendation would require more data and analysis than this author has available. The author has heard lower court judges describe this reform as another example of “building a cart behind closed doors (闭门造车).”

Back-end Issues

The crucial part of the “back-end” of judicial reform is analyzing the results of a reform, or more likely the multiple reforms that have been launched and considering whether further continuity is needed in the form of measures to sustain the reform or to compensate for problems that become apparent. The current judicial system contains many such unfinished judicial reforms. One example of an unfinished judicial reform is the role of the judges assistant (法官助理).* [The reform is now listed in point 41 of the Sixth Five-Year Reform Outline]. Law and Supreme People’s Court guidelines have not defined clearly the scope of a judicial assistant’s work. This lack of clarity has an impact on the operation of the entire judicial system. Reforms themselves need continuity.

Conclusion

It is a truism that Chinese judicial reform is a highly difficult and complex matter, as the brief discussion above has signaled. The development of a modernized judiciary depends on cultivating judicial reform specialists possessing the entire package of skills required to evolve and implement judicial reforms appropriate for all Chinese courts, whether they are urban or rural, large or small, specialized or general. These specialists need to combine deep local knowledge with that of international “best practices.” Reformers need to be able to focus on front-end and back-end matters, including accurately evaluating foreign experience, pilot projects, local innovations, and incomplete reforms. They also need to involve stakeholder input to the extent possible, so that judicial reform measures most closely fit the complex needs of the Chinese judicial system.

The author hopes that these views are useful as a whole or in part.

______________________________________

*The two examples of uncompleted judicial reforms mentioned above draw on the research and experience of Zeng Yuhang (曾宇航, STL 4L student, on family trial reform) and Xue Ye (薛偞, 2023 graduate of STL, on judicial assistant reform).

Many thanks also to Yuan Ye (袁野), PhD student at Peking University Law School (and 2022 graduate of STL) for transforming PowerPoint slides written in 洋式中文 into standard Chinese.

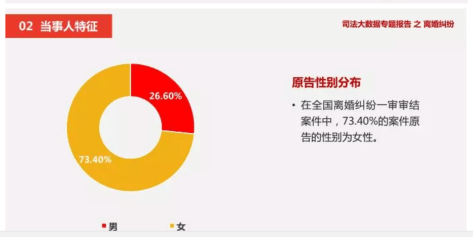

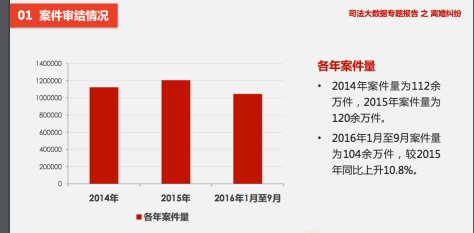

Almost three quarters (73%)of the plaintiffs in first instance divorce cases were women.

Almost three quarters (73%)of the plaintiffs in first instance divorce cases were women.

The rush towards year end in the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), as in the business world, means a flurry of announcements of important developments, to ensure that the SPC meets its own performance targets. Among the recent announcements are:

The rush towards year end in the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), as in the business world, means a flurry of announcements of important developments, to ensure that the SPC meets its own performance targets. Among the recent announcements are: Each month (as

Each month (as

You must be logged in to post a comment.