Susan Finder and Zhu Xinyue

Susan Finder and Zhu Xinyue

I. Overview of the 2023 SPC Work Report

Supreme People’s Court (SPC) Work Reports to the National People’s Congress (NPC) appear to the casual reader as much of a muchness. Like all official work reports, it provides a perfectly positioned overview of the previous year’s accomplishments and a high-level summary of 2024 work priorities.

To the attentive reader, the March 2024 SPC Work Report to the NPC (2024 SPC Work Report or Report) signals something new and different compared to its predecessor reports. This much-delayed blogpost flags only some of what is new. I have italicized many of my comments. (Please contact me if I have not mentioned your area of interest.)

The 2024 SPC Work Report signals that since President Zhang Jun took office, he has vigorously implemented new policies and set new priorities. Accordingly, the Report highlights Zhang Jun era keywords. Conveniently for the reader, they are contained in this single report. A single phrase or sentence in this report links to one or more SPC documents, initiatives, and guiding/typical cases.

As in previous years, local court cases or innovations are considered accomplishments and heralded on local court WeChat accounts. Last year’s report, in contrast, was President Zhou Qiang’s last and served as an official summary of his accomplishments over the previous five years.

Several phrases in the first paragraph of the 2024 Work Report (bolded) signal the new themes in this report:

… by focusing on the working theme of “justice and efficiency”, insisting on active justice, deepening and realizing service for the overall situation and justice for the people, we have made solid progress in promoting the modernization of judicial work聚焦“公正与效率”工作主题,坚持能动司法,做深做实为大局服务、为人民司法,推动审判工作现代化迈出坚实步伐…

As the regular reader of this blog could predict, the word “active ( 能动)” and the watchword or keyword “active justice (能动司法) can be found throughout the report.

Some statistics

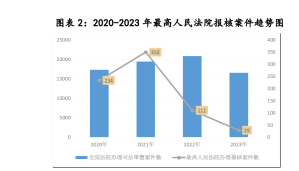

The initial section of the 2024 SPC Work Report provides overall statistics from the SPC and the entire court system. The SPC accepted 21,081 cases and concluded 17,855 cases, representing a year-on-year increase of 54.6% and 29.5%, respectively. These numbers reflect the end of the pilot project to reorient the four levels of the Chinese courts and the corresponding increase in retrial applications made to the SPC. It can be anticipated that those numbers will be even higher in the 2024 calendar year. As I have previously written, most of the civil and administrative retrial applications to the SPC are unsuccessful, but it requires SPC judicial time to review them. For Americans, a useful but not entirely appropriate analogy is the petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court.

The report states that courts at all levels accepted 45.574 million cases and concluded 45.268 million cases, with 15.6% and 13.4% yearly increases, respectively. Most cases in Chinese courts are civil/commercial (60.05%) or enforcement cases (29.34%). I would be grateful if a reader could provide comparative statistics (from other jurisdictions) on enforcement. My reaction is that the proportion of enforcement cases is relatively large. See the chart below:

These numbers likely are linked to the poor economy, which from comments by friends in the court system, means an increase in business disputes and business-related crime. These increases are evident despite policies to reduce the number of disputes entering the courts and resolve cases filed before they reach the hearing stage. Those policies include: resolving cases at their source, resolving others through mediation, (now promoted under the keyword/title of Fengqiao Experience), and promoting arbitration. Some judges have remarked privately that it also has to do with the low cost of litigation.

II. Serve the overall situation effectively and ensure high-quality development and high-level security with active justice

The title of this section combines several watchwords/keywords 提法/关键词, robustly signaling that President Zhang Jun led the drafting of this report.

The ten subsections in this section must be understood as ones that were priority areas for the Chinese courts in 2023. I have selected only a few of the subsections out of the ten:

Assisting the Strengthening of the Construction of the Financial Rule of Law

This subsection in the 2024 SPC Work Report is positioned immediately after the sections on safeguarding national security and social stability, promoting public security governance, and fighting corruption, reflecting its priorities in the SPC’s work. Although both the 2023 and 2024 SPC Work Reports address judicial support for finance, the 2024 SPC Work Report emphasizes strict regulatory enforcement in the banking and securities sectors, both subsumed under the category“financial trials.”

The Chinese courts concluded 3.032 million financial cases, an 8% year-on-year increase, and heard 861 money-laundering cases, involving 1,019 individuals, with increases of 23.5% and 22.2%, respectively. The money-laundering cases are likely linked to the ongoing multi-institutional anti-money-laundering campaign of which the SPC is a participating institution. The Report stresses the importance of “compliance in financial activities, strict punishment for senior management illegalities (高管违法要严罚), and holding intermediaries accountable for negligence.” The report illustrated the last two policies by mentioning a securities false statement case in which senior managers were found liable and an intermediary bore 20% joint and several liability. Given those signals, it will not be surprising that the Shanghai, Beijing, and Chengdu-Chongqing Financial Courts have made analogous judgments in 2023 and 2024. The allocation of liability in these cases is a current issue. The Report also mentioned two financial law-related judicial suggestions that the SPC issued, rarely, if ever mentioned in the past, linked to last year’s judicial interpretation on judicial suggestions/advice (司法建议).

Promoting the Development and Growth of the Private Economy in Accordance with Law

This subsection, new in comparison with last year’s report, links to the July 2023 Central Committee and State Council document on promoting the private economy, focusing on measures contained in a September 2023 policy document and typical cases. It includes a paragraph discussing the measures in that policy document and highlighting that the courts heard 42 cases of property rights-related wrongful convictions. The SPC issued 12 typical retrial cases (civil, criminal, and administrative) involving the rights of private enterprises and private entrepreneurs. Cases of bribery and embezzlement involving non-state employees amounted to 6,779, involving 8,124 individuals, with a year-on-year increase of 26.6%. Although the SPC intends to enhance legal certainty, boosting business confidence and stabilizing expectations, other sources report on profit-oriented law enforcement at the local level, often leading to the jailing of private entrepreneurs and the confiscation of their assets.

III Safeguarding and Enhancing People’s Livelihood through Active Justice

The section title above replaces “The Path of Judicial Services for the People With Chinese Characteristics” in the 2023 report.

New themes introduced include “Supporting Guaranteed Delivery of Commercial Housing and Stable Livelihoods,” to deal with issues related to the ongoing crisis involving real estate developers.

- Safeguarding Housing Rights: The financial collapse of many real estate developers has meant disputes along the real estate development supply chain. A 2023 SPC judicial interpretation prioritizes homebuyer rights, clarifying the order of claim repayment in disputes over unsuccessful delivery of sold commercial housing.

- Strengthening Housing Pre-sale Supervision: The SPC issued Judicial Suggestion No. 1 to promote contract online signing and pre-registration, enhance pre-sale funds supervision for commercial housing, strengthen pre-sale information inquiries, and warn about home buying risks. [These suggestions do not seem to have been made public.]

- Restructuring the Financial Chain of Homebuying: In response to a financial chain rupture of a private real estate enterprise in Hunan Province, a court-facilitated restructuring revitalized 16.8 billion yuan, resolving housing delivery issues for 16,000 households by facilitating the merger and restructuring of 13 related companies. This type of case was mentioned in a typical case that the SPC issued last year.

IV. Promoting National and Social Governance through Active Justice Which Practically Grasps the Front End and Treats the Disease Before it’s too Late

As could be anticipated, this section emphasizes judicial suggestions, among other matters.

Deepening the Effective Use of Judicial Suggestions: The Report emphasized judicial suggestions that fill legal gaps and governance deficiencies, mentioning the regulations on comprehensive governance-oriented judicial suggestions, discussed here. This is yet another initiative emphasized by President Zhang Jun. The SPC led with Judicial Suggestions No. 1 to No. 5, and lower courts issued 9,429 suggestions.

V. Ensuring Judicial Justice through Actively Performing Duties

This section underscores Party leadership within the judicial system, with the primacy of the Party’s political construction. It promotes “strengthening Party nature, emphasizing practical work, and achieving new accomplishments” (“强党性、重实践、建新功”) through solid “learning of ideology” (扎扎实实“学思想”) and outlines the result of “deepening investigation and research and solidifying thematic education”( 大兴调查研究,让主题教育走深走实) and implementing “investigation promoting case handling, and case handling also being investigation” (“调研促进办案、办案也是调研”).

The Report indirectly addresses public concerns about the China Judgements Online database by emphasizing efforts to improve transparency in judicial proceedings (裁判文书上网) and the “People’s Court Case Database”, such as posting 2.165 million documents online in 2023, with a year-on-year increase of 111.6%, covering a wider range of trial areas and case types, with the SPC and higher courts posting 35,000 documents, a 370% increase. The 2024 Report details measures for the uniform application of legal standards, including 15 judicial interpretations, 13 guiding cases, and 610 typical cases. As discussed here, the “People’s Court Case Database” contains SPC-approved cases, and judges must search this database. “Legal Response Network (法答网)” (analysis to come) launched on July 1, 2023, facilitates communication among courts and has received 280,000 legal application inquiries, answering 230,000. Insights from this platform have led to the revision or drafting of 27 judicial interpretations and regulatory documents.

More specific selected statistics

Bankruptcy cases: 29,000 bankruptcy cases were concluded, marking a year-on-year increase of 68.8%. Additionally, 1,485 bankruptcy restructuring and settlement cases were concluded. Local court white papers on bankruptcy (link is to the Shanghai court white paper) are an undervalued source of insights on more specific bankruptcy trends, such as the type of companies going bankrupt and the length the companies have been in business. One law firm report on bankruptcy flagged missingness on the SPC’s bankruptcy platform and the rate at which local courts accepted bankruptcy cases.

Foreign-related civil and commercial cases: 24,000 foreign-related civil and commercial cases and 16,000 maritime cases were concluded, representing annual increases of 3.6% and 5.3%. The average trial time decreases by nearly 10 days. 16,000 cases of judicial review of commercial arbitration were concluded, reflecting a 5% year-on-year increase. During this period, 552 arbitration awards were revoked, remaining stable year-on-year, while 69 foreign arbitration awards were recognized and enforced, representing a 16.9% increase. This section mentions a Shanghai Financial Court case in which the court stopped payment on a demand guarantee, although in fact most of such lawsuits are unsuccessful.

Deepening the diversification of dispute resolution: Since 2013, court cases have increased by an average annual rate of 13%, doubling over 10 years. Judges handled an average of 357 cases annually in 2023, up from 187 in 2017. The courts successfully mediated 11.998 million disputes through people’s mediation, administrative mediation, and industry-specific mediation organizations/institutions, representing a 32% increase year-on-year and accounting for 40.2% of the total civil and administrative cases filed.

Fully leveraging the role of scientific evaluation as a “command baton”: The annual case closure rate was adjusted to the closure rate within the trial period, which reached 97.7% last year, a 2 percentage point increase. A special case cleanup initiative concluded 1,914 lawsuits pending for over three years and 2,455 pending cases involving 6,909 individuals, accounting for 81.3% and 86.8%, respectively, of the total cases. The title of this section is significant. Judges at all levels of courts feel that “command baton.”

VI. 2024 Work Targets

As readers of this blog could anticipate, the 2024 work arrangements of the courts are focused on the modernization of judicial work, active justice, and other 2023 top keywords. The work arrangements listed here are more general than the types of work plans mentioned in my article. They are intended to signal to the NPC and general public the overall direction of the SPC’s work in the current year. For the most part, the arrangements are expressed in phrases or single sentences.

Criminal cases: Implement the holistic national security concept, severely punish crimes threatening national security and public safety, promote the normalization of crackdowns on gangs and evil [sometimes used against local entrepreneurs], and severely crack down on telecommunications network fraud, cross-border gambling, and corruption, with harsher punishment for bribery crimes. All if not most of these crimes were flagged during January’s annual Central Political-Legal Work Conference.

Intellectual property and digital rights: Strictly protect intellectual property rights and promote their transformation and application, and serve the development of new productive forces. Justice Tao Kaiyuan published an article in People’s Daily in late March explicating the link between the development of new productive forces and the improvement of intellectual property rights protection. Strengthen personal information protection and improve digital rights protection rules. The latter two presumably imply inter-institutional cooperation.

Bankruptcy and Economic Development: Increase work on hearing bankruptcy cases and give full play to “active rescue” and “timely liquidation”. We can expect to see the courts accepting more bankruptcy cases this year. Deepen the compliance reform for companies involved in criminal cases and continue to optimize the growth of the private economy. Properly handle real estate development and affordable housing contract disputes, and actively serve the new model of real estate development (recent Party/state initiative). Strengthen hearing and enforcement work in “agriculture, rural areas and farmers” (“三农”) to support rural revitalization. The latter is consistent with previous SPC policy.

Ecological and Social Justice: Serve ecological civilization [the environment] and green and low-carbon development in accordance with the law. Strengthen the protection of the rights of women, children, the elderly, disabled people, etc. (It is unclear whether that will include a better legal infrastructure for sexual harassment cases.) Strengthen administrative trials, supervise and support administrative agencies to administer according to law and strictly enforce the law. Promote judicial advice/suggestions and national and social governance.

Court administration. Improve the quality and efficiency of court hearings and accelerate the modernization of trial work. Deepen the comprehensive supporting reform of the judicial system and formulate the “Sixth Five-Year Plan” reform outline for the people’s courts. [It is unclear when it will be issued] Comprehensively and accurately implement the judicial responsibility/accountability system (see related documents here), and further implement “supervision/”review” system (阅核制) by senior court leaders. That system is one of President Zhang Jun’s initiatives. Improve the hierarchical selection system for judges and promote the coordinated use of posts and establishments across administrative regions. This seems to be a reform to share judicial headcount. Deepen the “three-in-one” reform of criminal, civil, and administrative cases in intellectual property, environmental resources, and juvenile matters.

Foreign-related and Grassroots Courts: Enhance the foreign-related judicial hearing system (consistent with my observations about the importance of foreign-related matters) and efficiency. Do a good job of “replying to letters and visits“, and strengthen the management of the source of letters and visits.

Grassroots Courts: Practice the “Fengqiao Experience” in the new era, promote resolving cases at source (诉源治理), provide practical guidance for mediation, and vigorously create “Fengqiao Style People’s Tribunals.” The SPC has issued six groups of related typical cases and the Chinese court media has begun to report on the creation of such people’s tribunals. The Report mentions strengthening relatively weak grassroots courts (相对薄弱基层法院), another initiative by President Zhang Jun. Under this initiative (full text of measures unavailable), 106 relatively weak local courts are targeted for additional support. The SPC has set quotas for each province, as well as a goal of removal from the list within one to three years.

Supervision, Guidance and Digital Courts: Strengthen supervision and guidance (stressed by President Zhang Jun, as mentioned above), deepen trial management, use the “People’s Courts Case Database” and improve the “Legal Response Network 法答网”. [More on this in a later blogpost, but it appears to be an updated version of letters to the 人民司法 (People’s Justice) mailbox)]. Develop a nationwide court “one network” and digital courts (数字法院) to boost efficiency. Note that the term “smart courts” (智慧法院), the subject of books, articles, and PhD dissertations in Chinese and English, appears to have been dropped.

Court Supervision and Integrity: The final section for the most part repeats principles seen previously, such as improving political, professional, and professional ethical qualities. It flags improving the training of professional trial talents in foreign-related, intellectual property, and other fields and stresses the use of personnel assessment of all court staff.

Finally, I conclude with this extended quotation from the Report:

the new development of the work of the people’s courts in the new era and new journey is fundamentally due to the leadership of General Secretary Xi Jinping and the scientific guidance of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. It has benefited from the effective supervision of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee, the strong support of the State Council, the democratic supervision of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the supervision of the National Supervision Commission and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the democratic supervision and support of various democratic parties, the Federation of Industry and Commerce, people’s organizations and non-party personages, and the enthusiastic concern, support and help of local party and government organs at all levels, deputies to the National People’s Congress, members of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, all sectors of society and the general public.

________________________________________________________

Many thanks to an anonymous peer reviewer!

References to “I, me or mine” are to Susan Finder rather than Zhu Xinyue. Finally, I’d like to express my appreciation to followers of this blog for their patience.

These journals are mostly published by the People’s Court Press (人民法院出版社). Some journals have local correspondents reporting on local developments. It can be surmised from how frequently a journal is updated how useful the relevant SPC division sees it as a platform for guidance and publicity of their views. Cases from these journals can often be seen reposted on WeChat.

These journals are mostly published by the People’s Court Press (人民法院出版社). Some journals have local correspondents reporting on local developments. It can be surmised from how frequently a journal is updated how useful the relevant SPC division sees it as a platform for guidance and publicity of their views. Cases from these journals can often be seen reposted on WeChat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.